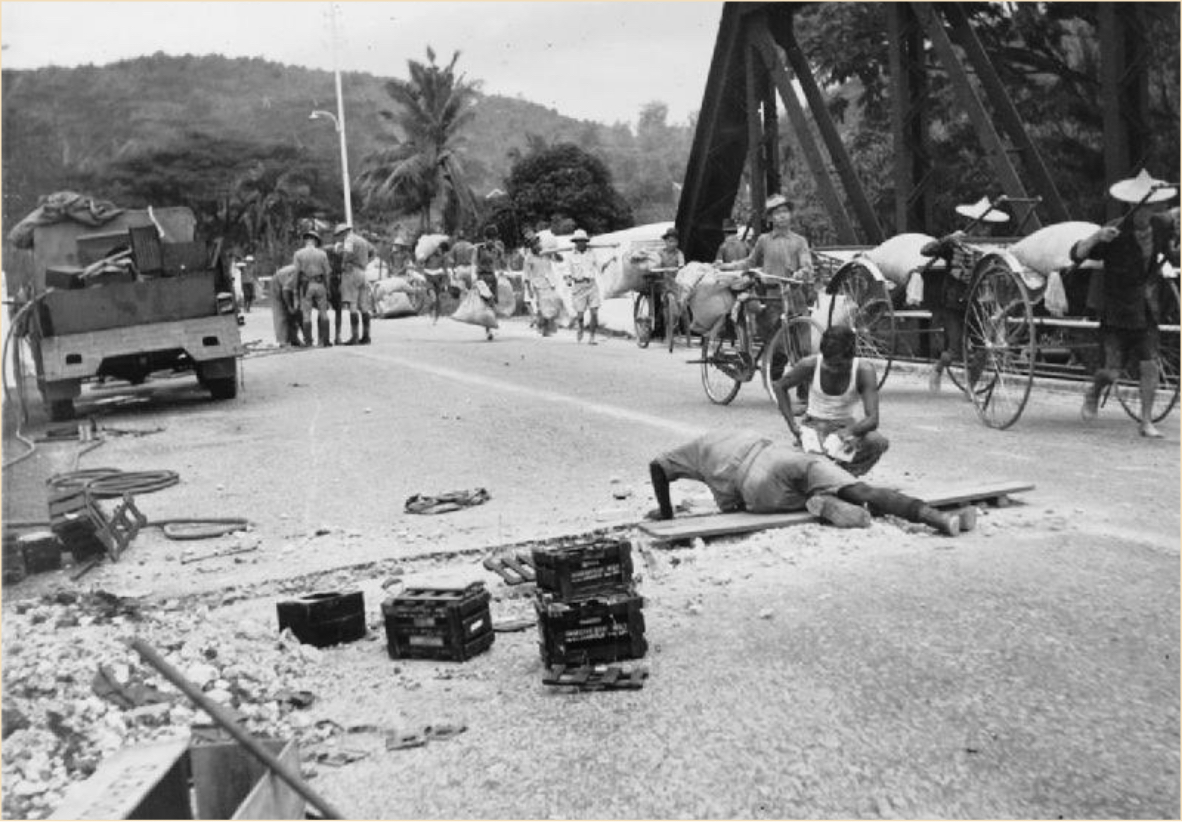

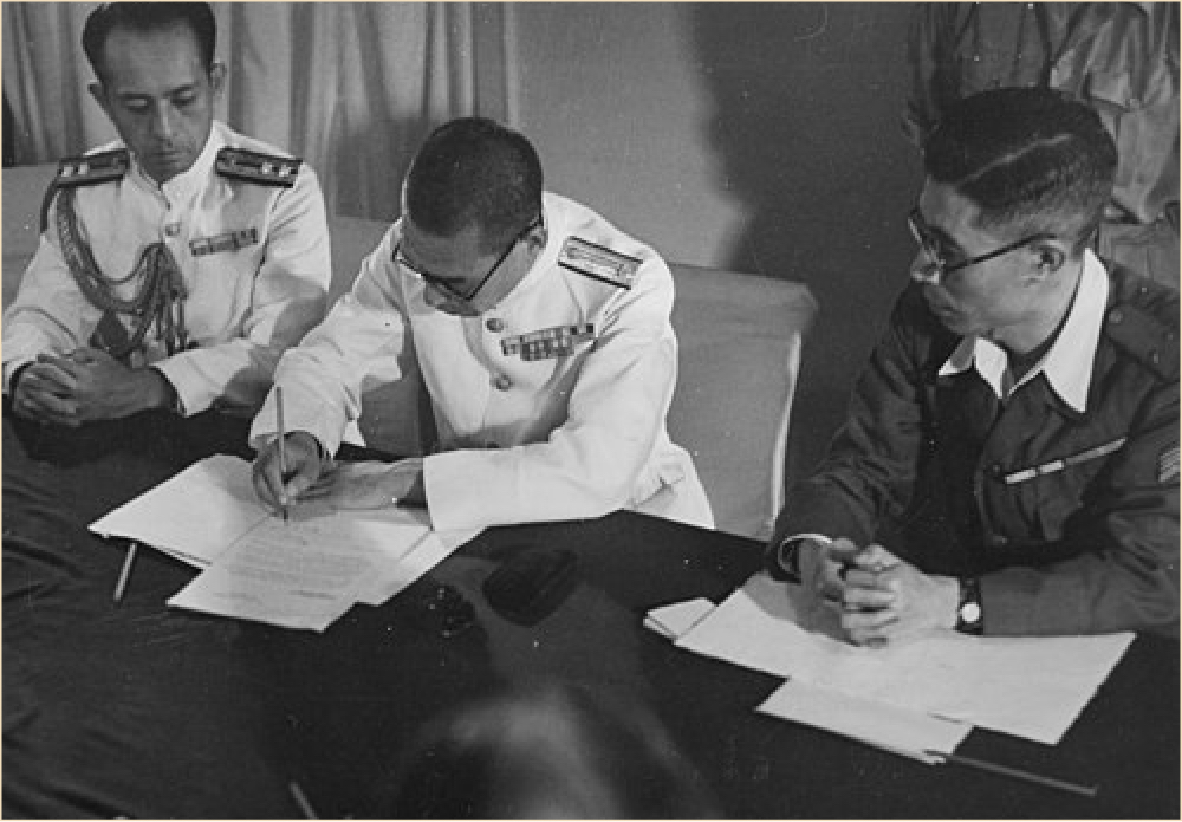

The Japanese invasion of Malaya began just after midnight on December 8, 1941 before the attack on Pearl Harbour when troops landed on the beaches of Kota Baru. While other countries have fascinating war museums and guided tours of WWII sites, memories of the war in Malaya seem to be fading away along with its last survivors.

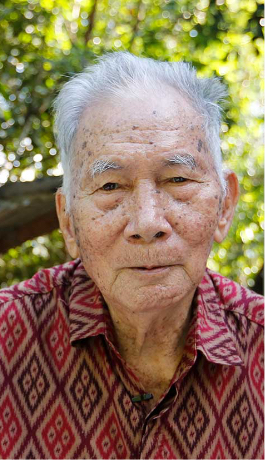

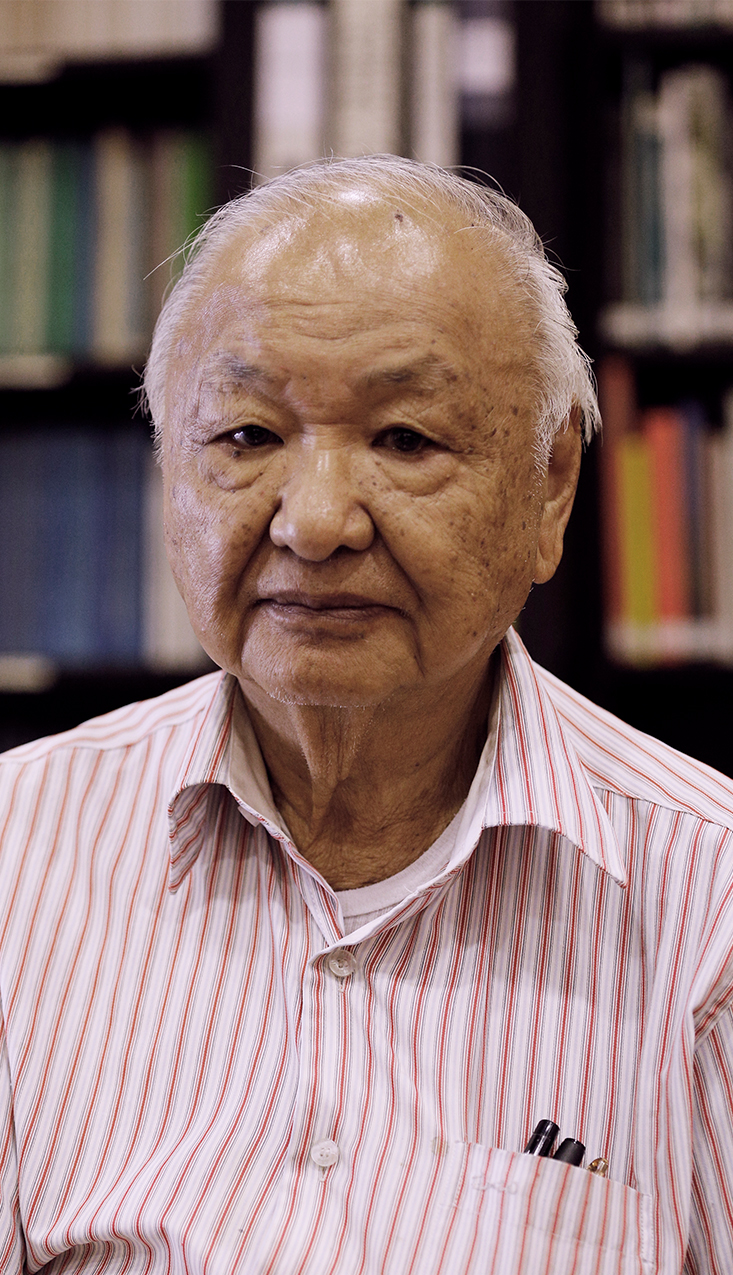

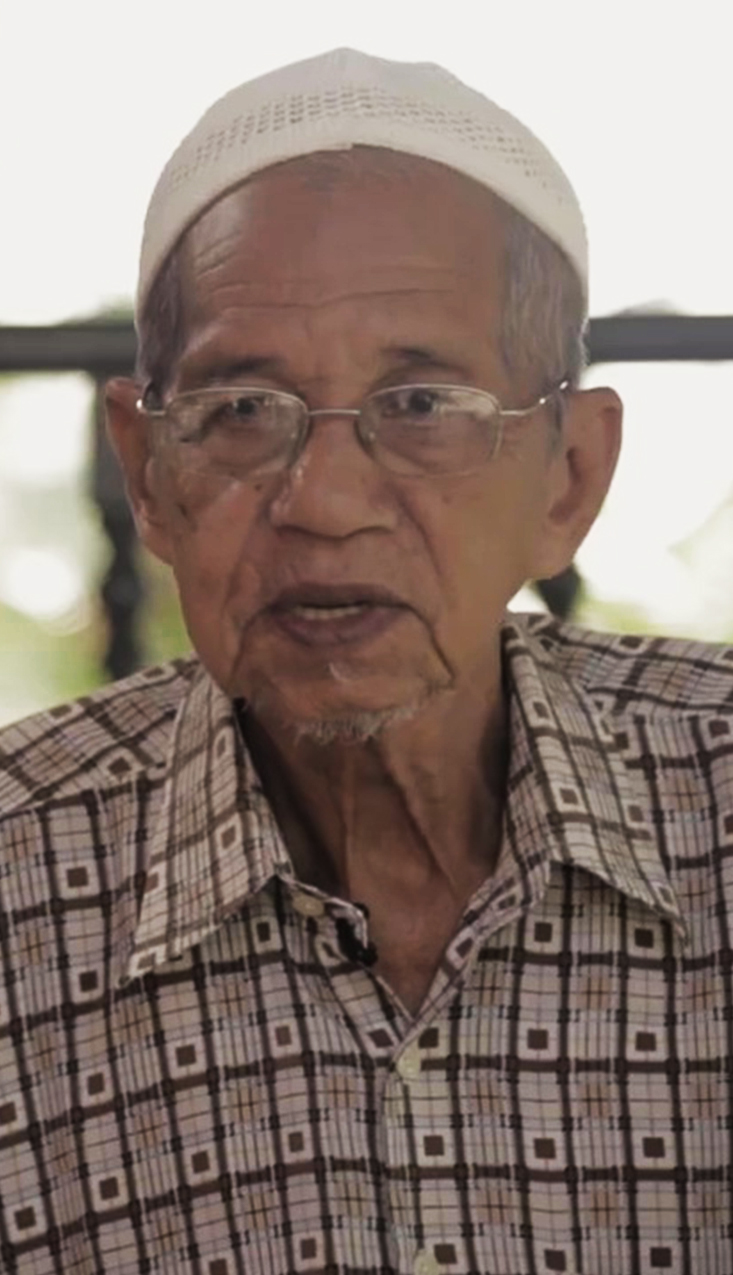

The Last Survivors is a documentary project that hopes to bring those stories back to life, by speaking to survivors of the Japanese occupation, and bringing them back to the locations which hold the deepest memories for them.