Inside the student trafficking trade

A network of deceit and exploitation that robs Bangladeshi college students of their money and education.

STORY BY Elroi Yee, Ian Yee, Lim May Lee and Samantha Chow

VIDEOS BY R.AGE

WE visit Samin under the cover of night, at his kongsi in Cyberjaya. Next to it looms the skeleton of an apartment block under construction. We walk past plywood-walled shacks and shipping containers, an open-air bathing area, up creaking stairs. He was ill that day, and wouldn’t talk to us.

We meet Farid at the warehouse he works at in Johor Baru. He shows us his work space, where he checks and records all incoming and outgoing stock. Where do you sleep? we ask. “I spread the mattress out here,” he motions to the concrete floor beside his work desk. He cooks his meals in a small corner of a storeroom, which he is too ashamed to show us.

To speak to Biplop, we pick him up at night from a mall in Sepang, and drive far away so his supervisor doesn’t see him speaking to us. We stay away from main roads to avoid police. There was once, he says, he had to hide in a dumpster to avoid arrest.

All three boys are Bangladeshis who came to Malaysia hoping for a college education, only to realise they had become victims of an extensive and elaborate human trafficking network stretching from Malaysia to Bangladesh. They’re now working illegally, saddled with debt and treated like criminals, with little hope of completing their education.

Over the course of their journey here, they have been cheated and extorted by college “agents” in their home country and Malaysia, and ignored by the colleges that are supposed to educate them. But to fully understand their story, we must first know Karim’s story.

It is broad daylight when we meet Karim, a 25-year-old Bangladeshi college student. He is sitting outside an international college whose eight-storey building stands conspicuous in a neighbourhood of low-lying shoplots. He seems happy to meet us, excited to try out his halting English. We learn that it’s his first week in Malaysia, that he’s an engineering student, and that he wants to travel Malaysia during study breaks. Maybe we can bring him around, he asks tentatively, if it’s okay with us. He loves Malaysia, he says bright-eyed. It’s beautiful.

Trafficking stories

Find out how Samin, Farid, Biplop and other victims were trafficked to Malaysia.

How it begins

THIS is where the cheating begins, with an education agent telling a prospective student just how wonderful it is to study in Malaysia. It’s modern, comfortable, and Muslim-friendly. All true, but the agent then adds lies and misrepresentations to his sales pitch. There are jobs ready and waiting for you. You can work part-time to pay for your education. The college is reputable. You can get a degree and get rich.

“Bangladeshi youths are desperate to study,” said Ashik Rahman, a Bangladeshi migrant rights activist based in Malaysia and founder of advocacy group Migrant88. “They see it as a means to escape the poverty and unemployment of the previous generation, and they prefer to study abroad because it comes with added social status.”

For years, Bangladesh has exported labour to wealthier countries like the gulf states, Singapore, and Malaysia, because its large, young population needs more jobs than its economy can offer. But as the local economy matures, in part because of foreign remittances from exported labour, demand is shifting from jobs to education. In a 2012 British Council report, Bangladesh’s tertiary enrollment was forecast to grow by 700,000 over the next decade, making it one of the ten countries with the fastest growing tertiary education sectors worldwide, a growth that the country is struggling to cope with.

It’s a situation ripe for exploitation. Preying on the students’ desperation, agents jack up their prices. For visa and college fees for the first year, they charge up to Tk400,000 (RM21,000). In Bangladesh, that’s equivalent to three years’ wages. Lured by false promises, some sell their family land or borrow from banks and loan sharks to make the amount. Samin and Farid both paid Tk260,000 (RM13,789). Biplop paid Tk300,000 (RM15,910). Karim paid Tk350,000 (RM18,562).

Arriving in Malaysia

THE next time we meet Karim, it is a month later on Hari Raya Aidiladha, and we take him and another Bangladeshi student on a quick tour of the city they so desperately want to see. First KLCC, then Dataran Merdeka. He loves every sight: “Bangladeshis call Malaysia the ‘Europe of Asia’,” he says as he poses in front of the Royal Selangor Club. He wants a photo there because a famous Bangladeshi singer filmed a music video against this exact backdrop. He joins a few other Bangladeshis for a short kickabout on the field. But when we ask him about his studies, a shadow passes over his face. He is reluctant to discuss the matter, but we learn that he applied to study an engineering degree, but found out that his college doesn’t even offer that course. His friend was more forthright: “The agent is a liar.”

The cheating continues the moment students like Karim land in Malaysia. Agents are either based in Bangladesh or in Malaysia. Either way, they would have representatives in the other country ‒ a Malaysian-based agent would have someone working for him in Bangladesh, and vice versa. When a student lands in Malaysia, the Malaysia-based agent takes over. Students rely on this agent, because they have little choice ‒ they don’t know how public transportation works, they have few friends if any to turn to, and they have a limited command of English. Just as agents in Bangladesh prey on their desperation for a better life, the agents in Malaysia prey on their vulnerability here. The lies never end, and the agent profiteers off the student at every opportunity.

At the airport, where immigration officers are under instructions to detain Bangladeshi students until college representatives arrive to receive them, agents often extort them for a little extra. “I waited there for two days,” tells Farid, the one who works at the warehouse. The agent wanted him to pay RM200 for “airport pickup”, but Farid refused on principle, arguing that it wasn’t part of the initial agreement. At the end of two days, with no food or water except what he could buy from overpriced airport stores, he relented.

More cheating followed. The agent took his passport to apply for a student visa. All international students, having been accepted by a local college, arrive in Malaysia on short-term single-entry visas. After they arrive, students need to submit their passports, academic records and a medical report to their colleges, who will apply for a student visa on their behalf. But Farid’s agent refused to return his passport until he paid an additional RM650. At every step, there is an agent telling him what to do and how much to pay.

Meeting a student trafficker

TO meet a college agent, we made up a factory. It would be a garment recycling factory somewhere in Kepong, where old clothes would be sorted, packed, and shipped to foreign buyers. An entirely imagined factory, of course. One of us would be a factory manager, looking to smuggle in migrant labour from Bangladesh through student visas.

“I brought in 8,000 students from Bangladesh,” the agent boasts. “3,500 was under ___ College, 2,500 under ____ College, and 1,500 under ________ Language Centre.” Since when? “Since 2013.” The agent is thick set, clearly non-Malaysian, with what seems to be a large scar under his left eye. His hands are stocked with expensive-looking rings and a gold watch. He claims to represent ___ College, a well-known college operating from a mall in the heart of Kuala Lumpur. Through further undercover work, we verified that he indeed works from an office within the college, and staff members refer to him for matters related to international students.

He tells us that 98% of the students are here as cheap labour, not to study. The agent continues to sell his services by telling us that class attendance can be faked for “a few hundred ringgit” to avoid problems with the Immigration Department.

“Every institute that gets the Home Ministry license (to enrol foreign students), they are looking for money. The only place to earn money is through Bangladeshi students ‒ bring in 200, 300 students, distribute them, your money come back already (sic). This is the way they do it.”

He admits that one of the colleges can no longer enrol international students, having had its international student license revoked a few years back for unscrupulously enrolling large numbers of Bangladeshi students, but he offers a solution: He can channel the students through other colleges.

“For colleges, we have ____ College, _____ College, _____ College,” he claims. “We also have a language centre. All of these are like our joint venture companies.” An ownership check on Companies Commission of Malaysia’s (SSM) registry shows that the directors at two of the colleges he mentioned are the main players in a separate business that offers “education consultancy for foreign students” on its website.

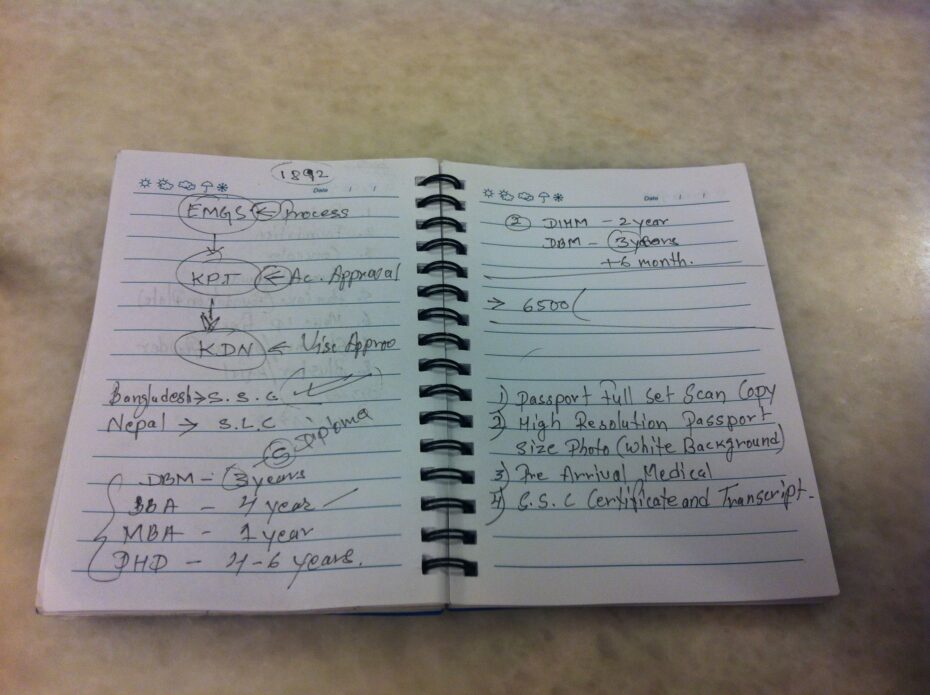

The agent goes on to sketch out on a notebook how he can give students visas for up to 10 years ‒ first enrolling them as language students, before offering them diploma, degree, masters and PhD courses. If the fees related to higher levels of study are an obstacle, he suggests that students enlist as diploma students, then drop out of courses before graduation and transfer to other colleges for another diploma course.

Meeting a human trafficker

R.AGE journalists go undercover to speak with student trafficking agents.

Trafficking through colleges

THIS is the root of the problem. All the colleges connected to this scam are clearly run for profit alone, to smuggle in migrant labour. The education of its students is barely considered. In a written reply to our queries, the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) confirmed that four private higher education institutions (HEIs) have had their international student licenses revoked since 2015. Officially, it was for rather generic reasons, but sources reveal that all four of the colleges were booked for unscrupulously bringing in large numbers of international students ‒ by the thousands ‒ with ___ College being one of them.

“It is up to (the agent) to make it clean the way he wants to make it clean.”

Other agents and college representatives we met undercover sell us the same line. One manager of a language centre in Kuala Lumpur claims he can offer up to three years’ visa by moving students around in different language courses. He also claims he can pay off immigration officers who come to check the centre’s premises. A college marketing representative we met through another agent tells us that his college, a mid-sized college, only takes “clean” students ‒ meaning genuine students with proper qualifications, but that “it is up to (the agent) to make it clean the way he wants to make it clean.”

Through nine months of investigations, we compiled a list of over 20 colleges that show signs of involvement in student trafficking. Undercover visits to some of these colleges reveal empty classrooms and deserted offices. Some colleges don’t even bother to set up classrooms, merely operating from small office lots. These colleges have become an underground system to recruit migrant labour, and genuine students are the collateral damage.

Mahfuz’s story

MAHFUZ’S eyes tear up as he speaks about his family. He had been defiant, determined, and even angry for most of the conversation, but the thought of his father, mother, and young brother back home in Bangladesh changes his tone.

“They don’t know what I do here in Malaysia,” he says in a combination of broken English and Malay.

“And why didn’t you tell them?” we ask.

“Pain,” he replies, patting his hand on his heart. “Pain.”

He is speaking to us at his favourite hangout spot in Kuala Lumpur, a Bangladeshi restaurant in the heart of the city not far from the gleaming Petronas Twin Towers, right behind one of the city’s most popular party streets. When it’s quiet, you can almost hear the EDM pumping in the air.

And yet, it feels like a different world. On this particular street, we’re surrounded by dilapidated low-cost flats, and everywhere we turn, we find victims of human trafficking. Just like Mahfuz.

“They don’t know what I do here in Malaysia.”

“And why didn’t you tell them?”

“Pain,” he replies, patting his hand on his heart. “Pain.”

Four years ago, Mahfuz was halfway through a four-year degree course at Michael Madhusudan University College in Bangladesh, studying philosophy. He then met a college agent who sold him an exciting idea. He could get a much more prestigious degree in Malaysia, and get paid much more working in KL, where there are plenty of great job opportunities.

Mahfuz’s family were desperate. His father had suffered two strokes, and could no longer work. His brother is only ten years old. Their hopes and dreams lie squarely on Mahfuz’s shoulders. So they took the deal. They scraped all their savings and even took out a loan to pay the agent. Mahfuz quit his degree course, believing he was doing the right thing for his family.

But it was all a lie. The college in Kuala Lumpur was fake. It didn’t offer any classes. They extorted Mahfuz for more money, then withheld his passport. There was no cushy job, there was no prestigious degree. Mahfuz was left to rot.

With no other choice, Mahfuz started working at construction sites so he could send some money home. And just like that, four years have passed. He could speak English once, he explains, but now he’s forgotten how. Four years in a construction site can do that.

Farid’s story

THIS is where the worst cheating happens. Genuine students, having paid exorbitant fees to arrive here, having been further extorted for more money at every step, finally realise that they will not get an education.

Farid tells us how his college was like: “I visited the whole college, and I didn’t see a single class in session. The classes are all empty.” He describes how there were many students waiting for their student visa documents, but most of them were in fact there for work, not for studies.

It was at the college that Farid realised he couldn’t study the course he wanted. He had asked his agent to apply for a course in software engineering, but in the college offer letter (which students receive in their home country, when a college accepts their application), he realised that he was only being offered a diploma in culinary arts. He questioned his agent, who told him he could apply to change his course when he arrives in Malaysia. The college flatly told him it wasn’t possible to do so, unless he sees out his current student visa and applies for a new one next year. That would mean paying another agent, again.

“I visited the whole college, and I didn’t see a single class in session. The classes are all empty.”

“I came for studies, only for my studies,” Farid says, angry. “But when I came here, I was disappointed.” His tone shifts to despair: “My dream has fallen down. Everything I thought before is now broken.”

Around the same time, Farid received word that his mother had fallen ill, and her medical bills are taking a toll on the family. Disillusioned and desperate for money, Farid chose to work so that he could recoup some of his family’s investment in his education.

From student to criminal

THAT’S how college students, cheated, extorted and now disillusioned, become criminals. Samin, a student at a college in KL when we spoke, has also resorted to working. He is an electrician at a construction site. His agent in Bangladesh peddled him one of the most common lies agents tell students ‒ he can work part-time while studying to pay for his education. Only when he arrived did he realise that working under a student visa is illegal.

“Anyone could be a victim of trafficking, not just labourers or sex workers. In these cases, the victims are students.”

According to Malaysian laws, international students are not allowed to work, not even part-time, except during long holidays, with special permission from their college and the Immigration Department. If caught, students face up to five years imprisonment, RM10,000 in fines, and even whipping. Worse, they would be deported at the end of the sentence, and their passports blacklisted, potentially barring them from seeking education in other countries.

It is an astonishingly common narrative among Bangladeshi students. Over the course of nine months, we logged over 30 cases where international students have been lied to, exploited, extorted, and left with no education. It’s a recruitment system that exploits the students’ vulnerability for profit. By definition, that is human trafficking.

“This is human trafficking, because all the elements of human trafficking are there,” explains Aegile Fernandez, director of migrant rights advocacy group Tenaganita. “Anyone could be a victim of trafficking, not just labourers or sex workers. In these cases, the victims are students.”

Ashik agrees: “Yes, of course this is human trafficking. Agents and colleges have all the power over these students, so they exploit them. It’s big business ‒ not just involving thousands of ringgit, but in the millions.”

It Begins in Bangladesh

WE followed the trail of exploited students all the way to Bangladesh. Here, in the frantic, congested, perpetually gridlocked capital city of Dhaka, we came across streets full of college students, easily identifiable by the college IDs around their necks or the backpacks on their shoulders, milling on the streets outside their colleges, waiting for their next class. Just next to Dhaka University, the country’s largest higher education institution, there is an entire market dedicated to producing, repurposing and selling secondhand textbooks. A sprawling complex of makeshift stalls connected by narrow alleyways, crowded with college students looking for books. This is clearly a country with a strong demand for tertiary education. And many are out to profit from this demand.

“Can you arrange a job for me if I get the visa through you?”

“We are sending you in student visa. But, if you want, we have our people over there who can help you for the job.”

We are listening to this conversation in a van, parked downstairs from a college agent’s office in downtown Dhaka. On this particular street, we see signboards advertising student visa services everywhere we look ‒ hanging from streetlights, crowded on shoplot facades, stenciled on walls, one was even neon-lighted at the top of a high-rise building ‒ and these signs often have logos of Malaysian colleges. We picked college agents from these ads, and sent an undercover journalist to meet them.

“You can surely work while you are in Malaysia,” the agent continues. “You won’t face trouble if you work while you study because you have all your (visa) documents as a student.”

This is the lie that trafficks thousands of students to Malaysia each year. Every agent in Dhaka repeated this lie to our undercover journalist. Some even encouraged him to work to fund his studies.

“What about attending classes?”

“Class schedule will be done according to your choice. Maybe you can attend classes two days a week. You can work the rest of the time.”

“We are sending you in student visa. But, if you want, we have our people over there who can help you for the job.”

Many have fallen for these lies. When we described the cases of student trafficking that we encountered in Malaysia to college students studying in Dhaka, none of them were surprised. Almost everyone knew someone who had been cheated while studying in Malaysia. Through our project partner, Bangladesh’s leading English newspaper The Daily Star, we interviewed three students who were recruited to study in Malaysia, paid exorbitant fees, but returned without an education.

One of them, a young lady, tells us how her college in Malaysia never held a single class. She was sent out to work in a restaurant as part of the college’s “internship programme”, and had her passport withheld by the college. Her husband who was studying (and working) with her, became undocumented after a year. He was caught by immigration officers and imprisoned for three months. Another student quit his course because the quality of the education offered at his college was too poor. We asked these students why they never reported their situations to the Malaysian authorities. Always, the reason they cite is fear.

Suffering in silence

AT night, at the end of the city tour, we send Karim home. We’re surprised when he tells us that he stays at an upmarket gated community just outside Petaling Jaya. Following his directions, we drive through the guardhouse, past rows of bungalows, past a landscaped lake with garden paths packed with residents on their post-dinner walk. But at a left turn beyond the glow of streetlights the asphalt turns to gravel, and we start to worry. Is this really where you stay? Yes, just further on, the entrance is on the right. Inside high zinc fences, in ramshackle blocks of plywood stacked two high, is where Karim is staying. It’s a kongsi. Apparently his agent, who has lied to him about his studies, is now putting him up at a construction worker’s hostel. We immediately advise him to lodge a complaint with Tenaganita, but Karim refuses. He’s afraid.

This is why the cheating will not stop. Traffickers continue with impunity because trafficked students have no safe avenue for redress, so they don’t lodge complaints against their traffickers. Most migrant rights NGOs in Malaysia are focused on migrant labour issues, not migrant students. Similarly, the Bangladeshi High Commission has not recorded a single complaint from students. MOHE has a complaints system, but most students don’t know about it, and it has only logged 20 complaints related to international students since 2013. Students also fear retribution from their colleges if they complain.

Because of this, there are no statistics available on how many students have been brought into Malaysia under trafficked situations, but one possible indicator is the number of Bangladeshi students in the country. Recent statistics from MOHE show that there were 30,657 Bangladeshi students enrolled in HEIs in Malaysia in 2015. That’s a third of the total international student population at HEIs, by far the highest in number, and three times more than the second-highest nationality. This does not take into account the countless students, who after being put into trafficked situations, became undocumented.

When approached by R.AGE for comment in Nov 2016, ministry officials indicated that it did not consider these students to be victims of trafficking, and that they have only received reports of “misrepresentation” by recruitment agents in the countries of origin. In a follow-up interview a month later, a ministry official flatly declined to discuss the issue, but issued a written reply denying that trafficking of students takes place. It was only when we managed to get Higher Education Minister Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh’s attention several months later that we started getting some answers.

“We discovered this was happening when our EMGS system picked up a surge in the number of Bangladeshi students,” said Idris. EMGS, or Education Malaysia Global Services, is the online platform that monitors and processes all international student applications. “We have taken action against nine colleges in 2016 and 2017, so the numbers have dropped. Only 1,100 Bangladeshi student visa applications have been approved so far this year, compared to 16,000 last year and 23,000 the year before,” he added.

International students enrolled in HEIs in Malaysia, 2015 (Higher Education Statistics)

“We discovered this was happening when our system picked up a surge in the number of Bangladeshi students.”

“We have taken action against nine colleges in 2016 and 2017, so the numbers have dropped,” – Malaysian Higher Education Minister Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh

Still, that means over 40,000 Bangladeshi students have been accepted to study in Malaysia over the past three years, and from what we’ve heard, almost all of them were trafficked, or at least victims of some form of exploitation.

And with the recent clampdown on undocumented migrants, many of these students, who are also undocumented now, are being hauled up for immigration crimes. The government had run a re-hiring programme to legalise undocumented migrant workers by granting them “E-kads” ahead of the clampdown, but remarkably, the agents found a way to use the programme to exploit their victims yet again.

Many student trafficking victims R.AGE spoke to saw the re-hiring programme as a way out of the situation they were living in. They were willing to pay supposed agents up to RM3,500 upfront, give them their passports, and pay another RM3,500 when their new visas are ready.

Tragically, Immigration Department director-general Datuk Seri Mustafar Ali confirmed to R.AGE that the scheme does not even apply to those on student visas. “If their purpose for coming to Malaysia is to study, then they have to study. After they complete their studies, they have to go back,” said Mustafar.

Of all the Bangladeshi students we met who applied for the programme, not a single one received an E-kad, and the deadline for applications passed on June 30. It’s common for agents to withhold passports from migrant workers to extort them for more money, so chances are the students will have to pay the agents the remaining RM3,500 anyway, just to get their passports back.

The good news is that both Idris and Mustafar are determined to set things right. Idris said MOHE will clamp down even harder on trafficking colleges and agents, and force them to pay for the victims’ education at another college. During a closed-door meeting with R.AGE to discuss possible solutions, Idris was visibly angered. “What these colleges and agents are doing is a sin! It’s sinful! I really feel bad for the victims,” he said, surrounded by some of his top officials. “But I don’t just want to use strong language. I want action. I want to put an end to this.”

Graduation day

THE last time we meet Karim, he had finally moved out of his kongsi, and was renting a flat with other Bangladeshi students. We meet him and two of his housemates at a hawker stall downstairs of his flat. He greets us warmly, but the excitement of being an international student ‒ learning the culture of a new country, meeting new people ‒ had completely dissipated. The moment we start conversing, we could sense the desperation.

“My head is very pressure,” (sic) he says. He uses the word “sick” a number of times to describe himself. He has long since realised there is no education for him in Malaysia, but returning home empty-handed after spending a fortune is unthinkable. His days are spent doing nothing, and his money is running out. He has only one realistic option. “I need job, I need work,” he says, imploring for help. “My head is not good.”

Next to him sat his housemate Hossein, newly-arrived from Bangladesh, smiling, excited to talk to us.

MORE FEATURE STORIES

A night in kongsi

R.AGE journalists spent a night in makeshift housing for construction workers, many of them victims of student trafficking.

Desperate in Dhaka

R.AGE journalists followed the trail of student traffickers from Malaysia to Bangladesh, where they found an entire industry dedicated to trafficking.

Student/Trafficked in the news

Aug 14, 2017 | Student trafficking network in Malaysian colleges exposed

Aug 14, 2017 | Coffee with a human trafficker

Aug 14, 2017 | Student trafficking to hit speed bump

Aug 15, 2017 | Bangladeshi community lauds R.AGE series

Aug 17, 2017 | Hope for trafficked student victims

Aug 18, 2017 | Higher Education Ministry determined to help victims of student trafficking

Aug 22, 2017 | We’ll help you, Zahid tells student victims

Sept 14, 2017 | DPM opens up on Malaysia’s anti-human trafficking policy

Nov 27, 2017 | Inside the dirty, dangerous world of Malaysia’s ‘kongsi’

Nov 27, 2017 | Adequate workers’ housing is basic requirement, says construction group

Nov 27, 2017 | R.AGE launches campaign to end student trafficking

Dec 20, 2017 | Five colleges and varsities back campaign

Mar 12, 2018 | R.AGE investigation follows traffickers to Bangladesh

June 23, 2018 | R.AGE wins major award, lobbies new government

A MESSAGE TO BANGLADESHI STUDENTS

ছাত্র/পাচারের শিকার

প্রতি বছর শিক্ষা এবং চাকরির প্রলোভন দেখিয়ে দালালরা হাজার হাজার বাংলাদেশি ছাত্রদের মালায়সিয়াতে পাচার করে।

এদের বেশীর ভাগরাই এবং তাদের পরিবার তাদের সর্বস্ব দালালদের হাতে তুলে দেয়, লাখ লাখ টাকা হাতিয়ে নেয় দালালরা। আর এই টাকা জোগাড় করতে অনেকে তাদের মূল্যবান সম্পদ বিক্রি করে দেয়, কেউবা জায়গা-জমি, যারা এটা এখন পড়ছেন তাদের বেশিরভাগই জানেন কেউ ঋণ নেয়, কেউবা তাদের বাড়ি বন্ধক রাখে।

দালালদের কাজই হচ্ছে মিথ্যার আশ্রয় নেয়া। আপনাদের অনেকেই হয়তো এই মিথ্যার শিকার। অনেকেই হয়তো একই পরিমাণ টাকা নষ্ট করেছেন এবং নষ্ট করেছেন নিজেদের জীবনের শ্রেষ্ঠ সময়গুলো এই মিথ্যার জালে পরে।

আমরা আপনাদের বলতে চাই যে আপনারা একা নয়। আমরা R.AGE এবং স্টার পত্রিকা কাজ করে যাচ্ছি আপনাদের গল্পগুলো তুলে ধরার জন্য, এবং আপনারা যাতে আপনাদের প্রয়োজন মত সাহায্য ও সহায়তা পান সেই ব্যাপারে আশ্বস্ত করতে।

আমাদের নতুন কাজ, “ছাত্র/পাচারের শিকার”, যেটাতে তুলে ধরা হবে আপনারা কিভাবে অবিচারের শিকার হয়েছেন মালায়সিয়াতে, এবং মালায়সিয়ার সব সচেতন নাগরিকদের আপনাদের সাহায্যে এগিয়ে আসার জন্য যুক্ত করা। আমরা যদি নাও পাই সবাইকে সাহায্যর জন্য, আমরা অন্তত তাদের কে বুঝাতে পারব আপনাদের অবস্থা।

আরো তথ্যর জন্য আমাদের ফেসবুক পেজ

facebook.com/studenttrafficked এবং

rage.com.my/trafficked

এ খোঁজ করতে পারেন। আর মনে রাখবেন – আপনি একা নন।

মালায়সিয়া আজ আপনার পাশে আছে।

TRANSLATION

Every year, thousands of Bangladeshi students are trafficked into Malaysia by agents promising them a college education and work opportunities.

Many of these students and their families pay a fortune to these agents, sometimes as much as four lakhs. To raise the money, some sell prized possessions, some sell land, some take loans and some remortgage their homes.

However, most of you reading this in Malaysia will know that the agents are liars. Most of you were victims of those lies. Most of you have wasted the same amount of money and the best years of your life because of those lies.

We want you to know that you are not alone. We at R.AGE and The Star have been working hard to make your stories heard, and to ensure that you get the help and support you need.

Our latest project, Student/Trafficked, aims to show everyone the injustice you have faced in Malaysia, and to get all concerned Malaysians involved in helping you. And if we can’t get everyone to help, we’ll at least get them to understand.

Find out more about our project at

facebook.com/studenttrafficked and

rage.com.my/trafficked.

And remember – you are not alone. Today, Malaysia stands with you.

Leave a reply