March 8, 2016

The Last Survivors: Your stories

The Map

Click on any pin on the map to read its World War II story. Red pins are stories by R.AGE, yellow are stories contributed by readers. If you have a World War II story you’d like us to upload to this map, email us (alltherage@thestar.com.my) along with the exact location of your story on Google Maps.

Pictures of locations from during the war or comparison pictures can also be emailed to us.

Video submissions are encouraged so get out there and talk to a survivor. Interesting stories and videos stand a chance to be filmed as an episode of The Last Survivors.

N. Pushparani

A child of six years during WWII was not at all bright as her peers of today. She could have heard of the telephone but would not have known how it operates. But what she sees, hears and experiences are all stored in her memory bank with a lifelong expiry date.

Life was normal for me during the WWII era because I grew up in that sort of environment, but it was not normal at all for others who were much older than me. It was mere hardship, in Sungai Siput during WWII.

One morning my mother wanted to make coffee but there were no matches to light the stove. My father had to go out to get the matches from the shop. When he stepped out of the house, he saw a man in uniform with a gun in his hand, waiting at the junction that was about 100 metres from our home. He knew it would be unwise to backtrack, as it would raise suspicions. Besides, it was quite normal to see soldiers all over the place. But my mother’s face paled at the sight because my father had to pass the soldier before he could get to the matches. She might have thought that the soldier had a shoot on sight order. The older generation had witnessed lots of ‘shoot on sight’ episodes that sent chills down their spines.

When my father passed the soldier, the soldier beckoned to my father, whispered something to him and then let him go. When my father passed him again on his way back from getting the matches, the soldier again told him something. My mother and I were watching from the porch of our house. When my father came back to the house with the matches, my mother heaved a big sigh of relief. To mother, it was like my father had returned home after a long and dangerous journey. The thought that everything was over and we could have the coffee was short-lived when my father said we had to go to the Big Field near the HA’s (Hospital Assistant) house straight away.

We hurried to the Big Field without our morning coffee. When we went to the Big Field we saw many others walking towards the field. The controlling soldiers made us sit down. It was an open field without any trees around for shade. I didn’t know what was happening and decided to look out for my friends (ignorance is bliss!). On the other hand, fear was written in block letters on the faces of the older generation. They must have had bitter experiences in life. They were looking at one another for answers.

It was a hot day and there was no shady area to sit in the field. I remember this part very clearly because I was very hungry. I got to see my father in the late mid-day, and he brought good news. He said all of us could go back home. He also said that the HA’s family minus the HA would be living with us. Both my father and the HA had work to do.

Both families lived upstairs in the Estate Manager’s big bungalow quite comfortably. I do not know what happened to the manager. He was a ‘white’ man. Numerous Japanese soldiers occupied the lower floor and it was always very noisy. When I put my ears to the wooden floorboard the resonant sounds were like thousands of white ants having a field day munching up the wooden floorboard. It was that noisy downstairs.

I don’t know how long we were living in these conditions. When most of the soldiers were away on duty I had the courage to go downstairs. There was a staircase in the bathroom upstairs that led to the kitchen verandah. I used the staircase to go down but if I saw any soldiers around, I would run back upstairs.

One fine day, we were surprised to find downstairs quiet and empty and our fathers had returned home. That was when we knew that the soldiers won’t be back and our fathers were working for the Japanese in the Dispensary. My father was assisting the HA to take care of the wounded and run errands for the Japanese. The HA’s house was being used as a mini hospital.

The HA’s family went back to their house and we stayed on in the bungalow until I was eight years old. However, most of the time, my mother and I would stay in Ipoh with my aunt and uncle. I was one of the luckier ones as sadly, some of the children’s fathers never came back home.

I remember the bungalow being surrounded by paddy fields (Hill Paddy), millet (Ragi), corn, tapioca and vegetable plots. These became our staples. The labourers were mostly women working in the fields as their husbands were sent to Siam (Thailand) to build roads, bridges and rail tracks. Eventually, some of the menfolk returned to Malaysia. At the time, the most common mode of transport was bicycle and bullock cart. One could see men pulling rickshaws in the town area as their livelihood. Cars were scarce on the roads.

These memories from 71 years ago are well-entrenched in my mind and still linger in my mind even till now.

The author, N. Pushparani at 13.

Casey Liu

During the Japanese occupation, many local Chinese contributed money towards the nationalist government of China, and my father was no exception.

One day, the Japanese came to our two-storey shop in Sitiawan, Perak and they picked up a tiny badge on the floorboard upstairs. The badge was given to my father in recognition of his periodic financial contribution to the Kuomintang.

My father was interned in the local police station and confined in a foetal position under a big jar. My sister-in-law, who was still in her teens, cut her hair short, dressed like a man and accepted the enormous risk to look him up at the police station.

My father was eventually released after a few days of confinement, and he immediately searched the house for any other incriminating documents and souvenirs. These included all documents printed in English. All were consigned to the flame without exception.

That is how none of us eleven siblings possess birth certificates or any identity documents.

My sister- in- law Mdm Lam, now 87, is an Alzheimer’s patient under the care of her daughter and the Ampang Hospital.

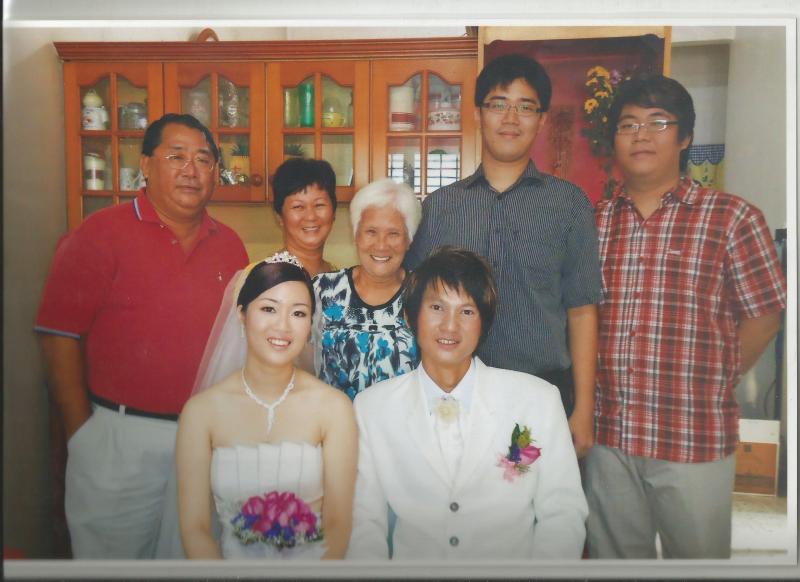

The author’s sister-in-law Mdm Lam at her 80th birthday, together with family members in Sitiawan.

Melissa Yew from Kuala Lumpur

My mum Tan Thai Hong is one of the last survivors. She is 87 years now and lives in Bukit Mertajam, Penang. She was born in Singapore but grew up in Kulim and Bukit Mertajam.

She used to tell me about her childhood memories over and over again. There are a lot of sad episodes especially during the Japanese period.

She was about 10-15 years old when the Japanese came. At that time, her father passed away due to illness and my grandma had to work as a part time maid for several rich households, including my dad’s home. My grandma also made tofu to sell at the wet market in Nibong Tebal and later Bukit Mertajam. My mum said they were so poor that they didn’t have rice to eat sometimes and would eat unsold tofu. My grandmother, being a typical China woman, still had children in China and sent all her savings back to China, leaving them poor here.

Mum said the Japanese soldiers were very “hum sup”, always looking for young girls and my grandma had to hide my mum in a big drain. During riots, they would run into the jungle to hide. It was always about fear and hiding growing up.

She mentioned about:

a) Switching off lights after a certain time, I think was after 7pm

b) Japanese soldiers would beat you if they find one cent coins in your house. I think at that time the Japanese wanted to collect as much metal.

c) Queuing up for rice

d) Beating up men they thought were traitors or people they simply didn’t like. The Japanese soldiers would use water pipe to pump water into their stomach and then step on their stomach. The house that the Japanese used for such activities is still around and is located in Jalan Asmara, Bukit Mertajam. According to my mum, that house is haunted with a lot of sad souls/spirits.

e) Several “padang”/fields , are areas where they shoot traitors. One of them, she said, is the “Jacobs Greens” in one of the boys school in Bukit Mertajam.

Because the Japanese were looking for young girls, my grandma decided to marry my mum off to my father as his second wife. They had no choice as my grandma was poor and was tired of hiding my mum as she is quite pretty.

But another reason why my grandma decided to marry my mum to my dad was because my dad would be able to protect my mum as he was a mechanic, who owned a workshop in town, where he was forced to repair the Japanese’s vehicles. And since the Japanese needed him, they didn’t harm my dad or his family. My father’s workshop was called ‘Yew Loh Sin’s motor repair shop workshop’ and is featured in the book ‘The Unsung patriot of Wong Pow Nee’.

I guess why the younger generation isn’t interested in such true stories could be because they are all sad stories about living in fear, torture, and poverty.

This is all I can remember from what my mum has told me.

Tan Thai Hong (right) at 16, with a cousin.

Han Wei Ming

Good job on this feature. Loving it.

If any of you is well versed in Penang Hokkien, you might want to hear my aunt’s stories. Location: Tanjung Bungah/ Tanjung Tokong, Penang

There were stories of her having difficulties getting food ration because she was short while everybody else towered over her, hiding under the bridge while trying to muffle my second aunt, who was crying, as the soldiers walk above, her neighbourhood friends hiding guns in the atap roof and was eventually caught (a speculated double agent story here) and the villagers being punished for not bowing to japanese soldiers as they march by…

I’m pretty sure I’ve mixed up the stories I’ve heard. They are from during Japanese occupation and post war/communist era.

John Robson from Kuala Lumpur

I am 84 years old and I can recollect the day I witnessed how three Chinese people were beheaded at the old Pavilion Theatre roundabout, directly below the Police H.Q. The Japanese Major I think pulled out his sword and asked all the public to watch. He went to the first Chinese, who was kneeling blindfolded with a white cloth, and with one swing he slice the head off. The body fell forward twitching and turning. It was a sight I can never forget till this very day.

He then went over to the second person with his sword covered with blood and swung his sword but the sword missed the neck and struck the top back of his head. The man screamed and started to roll on the ground, the Major asked his men to hold him but his men was a bit reluctant. They had to obey the order and held him up. The second swing cut his head off.

The third Chinese man started to shout for help. The Major swung his sword this time and with one stroke, it cut off his head. All the heads were then put on a bamboo stick for all people to see. The public must stop and bow in front of the heads before walking past. The Major accused them of being spies for the British. During the Japanese occupation, I have worked and seen many cruel things.

I am now residing in Ipoh. What I have seen can never be forgotten.

Mohd Iqbal Hashim from Ranau

I may have someone who you might be interested to interview: my grandma. She’s from Ranau and she survived the Imperial Japanese occupation of North Borneo during the war. But the one thing that will make her story interesting is that when I was still a kid, my mom would always tell me how my grandma took them to hide in a hole whenever she heard propeller engine planes in the sky. I was confused like why a hole? It seems illogical. But then when I learned the history, it all made sense. Those planes were there not to shoot their targets, but for carpet bomb/fire bombing campaign.

Doreen Lim

Hello my father Mr.Lim Chung Bee will be 93 this year and he was a prisoner of war (POW) in Japan from 1942-1946. He is staying in Bukit Jelutong, Shah Alam with my brother Mr. Lim Choo Hock. Perhaps you may want to refer to Senior Star 2, Wednesday 3 October 2012 to read a bit about this remarkable Peranakan Baba who was a POW at the age of 17. Today he’s still mobile. He sometimes talks about the war and the Japanese occupation. It’s something he will never forget, forever etched in his mind. Hope you will give this a thought and visit him because I think he is one of the last survivors.

Yatasha Yusof from Cheras

I write this email on behalf of my grandfather. His name is Johari and was born in 1930. He was reading your column (TLSWWII) and is really interested to share his experience with your team. In fact, he appreciates your team’s effort in compiling and documenting all these history.

My grandfather is a pensioner from one of the government uniform body. He really enjoys reading and watching television after his retirement. Last night, he asked me to email your team as he wishes to share his stories.

During the WWII, he was in Banting, Selangor. He wrote down some of the events in chronological order for your reference:

Dec 7, 1941: School holiday (Schooling at High School, Klang) – staying with family at Kg. Kelanang, Banting

Jan 1942: The Japanese invading force reached our kampung, searched our house, took away a bicycle and a watch

Feb 15, 1942: The British surrendered

May 1942: School reopened, Malay school taught Malay and Japanese language

Sept 1943: Left school

Oct 1943: Worked as a labourer at the Japanese Naval Shipyard in Telok Datok, which is now Stadium Jugra

Sept 1944: Worked as a telephone operator at the post office in Batu Laut. He served the Japanese military camps that were located on the coast between Morib and Port Dickson

Sept 9, 1945: Witnessed the British forces landing at Morib

Sept 30, 1945: Service as Telephone Operator terminated

Choo Xin Er

Seventy five years ago, my grandmother chopped off her long locks, and exchanged her dresses for her brother’s trousers. But it was no symbol of teenage rebellion; instead, it was a disguise from the preying eyes of the Japanese soldiers.

Grandma was 11 years old when the Japanese invaded her hometown in Penang. The occupation marked the end of her education, and rumors of young girls being captured and raped soon made their way to her peaceful neighborhood in Nibong Tebal.

Worried for her daughters’ safety, my great grandmother ‘transformed’ all the girls in the family as boys, and left home for Kampung Tiga Ratus Kaki, a small village in Kedah.

“I remember feeling very scared, carrying my baby sister, running to board the bus,” my grandma said. “My mother sewed each of us a cloth belt which we wore underneath our shirts to hide money for emergencies.”

Back in Nibong Tebal, my grandma’s family ran a sundry shop. Business continued as usual during the occupation, but she recalls the day when her father stormed in, furious, announcing that he wanted to close the shop.

“A Japanese soldier had come in and bought biscuits,” she said. “When my father asked for payment, the soldier got angry and hit him with a bayonet.”

There were no serious repercussions from that incident (the shop reopened soon after); however, my great grandfather still ended up as a victim of the occupation. An alleged local Japanese ally blindfolded and captured him, before taking him to an unknown location for one or two nights.

Whatever happened to my great grandfather on the fateful day would forever remain a mystery. Eventually, he was released unharmed, but as a changed man. Fear constantly gripped him, and he was depressed. One day, he went to a friend’s house for the night – and was found to have hung himself in the kitchen the next morning.

It was a grim example of how the worst injuries are often not physical but psychological, and their effects can be shattering to their loved ones.

“Ever since the day my mother received the call informing her of my father’s suicide, she would get panic attacks whenever the phone rang,” my grandma recalls.

Despite the traumatic incident, my grandma considers herself lucky to have survived the war without experiencing any violence first hand. The war had shaped her into a resilient and determined woman, unfazed by any challenge life throws in her way.

Chan Vy Sing

I enclose herewith a short write up by my father on his recollection of the war on the topic of “Escape from the Japanese bombing and arrest”.

(I) On the morning of Christmas eve 1941, Japanese warplanes bombed Port Swettenham (now Port Klang) and while flying out, they bombed Klang Town where I happened to be at the time. The bombing blasts were ferocious, shaking the ground vigorously and sending a hail of shrapnel. The atmosphere was clouded with thick phosphorous fumes. Then there was a brief moment of eerie silence broken by the noise of raging fire and the cracking of buildings. Screams were heard and people, including myself, started running away from the devastated area to safety.

Fortunately, I had earlier heeded the instruction of the A.R.P (Air Raid Precaution) by lying flat on the ground underneath a table as the best possible means to avoid injury or death in case of an air raid. Fortunately, I had survived this Japanese bomb attack.

(II) During the early stages of the Japanese occupation, I was a young schoolboy and naive. I was listening to the Voice of America “Double Ten” radio broadcast one night on October 10, 1942 when an armed Japanese soldier patrolling in the vicinity barged into the house on suspicion of the radio noise. He checked all the rooms in the house except the room I was in with the radio. I was very frightened thinking of the consequences of arrest.

After a short while, the Japanese soldier left and I felt relieved for having avoided arrest by the Japanese.

(III) Some months later, I skipped my night Chinese language private class held at Meru Road, Klang. On this very night, the Japanese Kempetai (Japanese secret police) raided the class on suspicion of subversive activities and arrested the teacher and some students. They were imprisoned at the Pudu Gaol in Kuala Lumpur for the duration of the war. I was told some of them died from torture.

Luckily I had again avoided arrest by the Japanese.

Eugenie Lariche

Born Eugenie Hermoine Lariche in Taku Estate Kelantan on 28 December 1927 to Andre Lariche & Catherine Rocke (parents), who originated from Kurumbagaram, Karaikal (French Territories) Chennai, India. I am second in a family of four siblings.

My father worked in Budu Estate Kuala Lipis, Pahang, as Chief Clerk. In 1936, my mother and we 4 children returned to Malaya in 1936. After primary school I moved to Sacred Heart Convent Bandar Hilir, Malacca until 1941.

When war broke out, the Japanese planes attacked our estate (Cheriot) in December, killing a cow (the bomb landed in a cowshed). Most of the workers and supervisors ran out of their quarters screaming, running helter-skelter to seek shelter. Soon after they started bombing Kuala Lumpur, with some of our relatives becoming casualties.

After a few days, the Japanese came to the estate looking for the British managers, who had fled with their families. My father was recruited by the Japanese along with most of the male estate labourers and sent to work at the Malaya-Siam border (Isthmus of Kra) – what was to be known as ‘Death Railway’.

We the family of 5, mother, 3 girls and 1 boy were left to fend for ourselves. My mother was 37 years, and the children – 15, 14, 12 and 10 years old. I attended Holy Infant Jesus convent in Seremban for a while, but everything was in Japanese.

My father fell sick in Thailand, having lost weight from eating plain rice, salted fish and green peas everyday. He was also covered in boils. After reaching Seremban he was sent to the General Hospital there, and took a long time to fully recover even after his discharge.

Soon after the whole family was made to work in Kuala Lumpur Hospital (HKL), where we all did different tasks – carrying food, folding bandages, working in the wards etc.

After the Japanese surrendered, most soldiers and doctors committed suicide – hara kiri. We shifted back to Cheriot Estate Negeri Sembilan and went back to school in Malacca Portuguese Convent.

We thanked God for being kind to us. But alas, most of the estate workers (men) died in Siam and their families went through a very tough time.

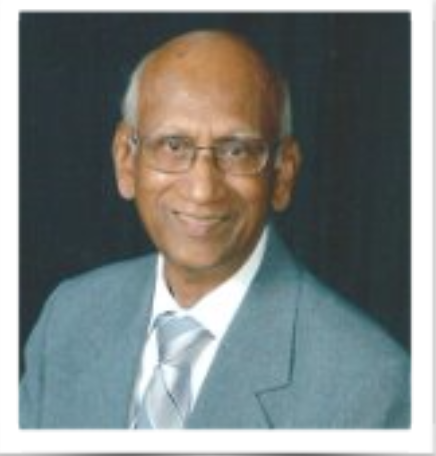

Eugenie Lariche, 1958

Patricia Lariche

I was only 12 years old when the Japanese invaded Malaysia in 1942. I have

two sisters older to me and a younger brother. Although I am 87 years old now but I have a vivid memory of the miserable life we went through during the Japanese occupation.

My dad was working as a chief clerk in Cheviot Estate, Seremban. Whenever the Japanese soldiers returned from their campaigns, my mother would hide us in the toilet, fearing they will rape us. In 1942, my dad was asked to go to the Siam border (Isthmus of Kra) as part of a labour force to build the railway, which was known as the infamous ‘death railway’. Most of the labourers were tortured and died as a result. In 1944, my dad returned to Malaysia in a terrible condition suffering from a skin disease. He had sleepless nights. He was also put in prison for no rhyme or reason.

We lived on tapioca, sweet potato and ragi. We had no rice, milk and sugar.

To make things worse, my mother was gored by a cow, and was admitted to General Hospital Seremban and underwent an operation.

I will never forget the hardship my parents went through and the atrocities

committed by the Japanese soldiers. I am still waiting for the compensation for the next of kin.

Patricia (standing, far right) and her family.

Vicky Chia

This story was told to me by my husband’s late grandmother. She was in her early twenties during WW11. Their house is in a remote village. The family would stay in the house during the day time but when night fell, they would sleep in the jungle nearby until day breaks.

There is also the story of my late grandfather’s encounter with the Japanese, as told to me by my mother. All need to bow on seeing the Japanese soldiers as a form of respect. On one occasion, they accused my grandfather of not bowing and forced him to hold up his bicycle high in the air as punishment.

Julz Ahmad

Reader Julz sent us in this story about her (now) 80-year-old father:

My father lived at the railway workshop in Sentul – he experienced many bombings by the Allied forces.

He saw the Japanese torturing the locals in public near the Sentul shophouses for using counterfeit money.

He was also attending a school in Segambut and on the way there, there was a lot of blood on the road one day. He stopped going to school after this.

His father (my grandfather) was also sent to the Burmese railway as he was a railway clerk. He tried sending bags of rice through the railway system occasionally. They had shredded tapioca and rice when this happened.

Yap Gaik Swee

DURING the Japanese Occupation, it was common to hear stories of death, torture and cruelty inflicted by the Japanese.

But it is the rare moments of kindness that remained in people’s memories.

Yap Gaik Swee, 96, still remembers the day a Japanese military truck almost ran her over during her daily milk delivery rounds on Jalan Chow Kit in Kuala Lumpur.

“I was so scared as they approached me, but to my surprise they picked me up and gave me money in compensation for the wasted milk.”

Yap said she was terrified despite their kindness, though it made her realise not all the Japanese were cruel.

While her husband worked as a government servant in the Malaysian Meteorological Department, Yap was busy cooking and distributing milk to families in need. Her husband also helped out with the deliveries.

“I used to buy fresh milk in large quantities and cook it in a pot with sugar,” said Yap.

Although times were hard, she made sure those less fortunate were able to have some sort of sustenance.

“Even though people asked, I made sure the milk only went to families with children, who needed it more.”

Every day was spent cooking and delivering milk, on top of looking after the family.

Her family bungalow was located on Jalan Ipoh, behind the shophouse she and her husband lived in.

In her late husband’s notes, he recalled listening to the radio in secret at the bungalow every night, catching the All India Radio Broadcast which gave updates on the progress of the war. After listening, the radio would be dismantled and hidden in the ceiling.

Yap still remembers the end of the war. The British was bombing Japanese-controlled railway lines, and her home in Sentul was nearly bombed as well.

Yap in her mid-twenties, after the war

Kee Ah Lek

Kee Ah Lek’s granddaughter, Zara Hamzah Sendut sent in this story:

My grandmother was a 10 year old student when she underwent the traumatic experiences of the Japanese invasion in Ipoh, Malaysia. “Everybody was afraid of the Japanese” she said. “The Japanese would force you to kneel up to the government office. If you didn’t kneel, they would whip you.”

Kee, like any other child at the time, was petrified. When passing a sentry post, you would have to bow. “Everybody had to bow. I also bowed a few times.” She also saw human heads hung up in the Ipoh market to show you what would happen to you if you didn’t obey.

During this time, a lot of people were in favour of the communists. In the villages, people would secretly “put rice underneath the fence for them [the communists].” It was a very risky task. “If the Japanese caught you, they would shoot you.”

In addition, Kee and her siblings had to hide among the grass in Papan, Perak. “We had to hide from the Japanese who were using their swords to sweep the grass for people who helped the communists.” If the Japanese found you, they would chop your head off. The girls were forced to cut their hair short and dress up like boys. Luckily for my grandmother, she “didn’t have to dress like a boy because she was still young.” However, her older sister had to.

Kee, now 86, is living in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Wong Shue Tuck

Now living in Canada, professor emeritus Wong heard about The Last Survivors from a relative in Malaysia.

Responding to our shoutout for video submissions, Wong sent in a video of his wartime experience in Seremban.

“When I was eight, I was forced to become a farmer, growing crops in an abandoned tin mine,” said Wong.

His father was also arrested by the Kempeitai, the feared military police mentioned in fear by every survivor we’ve spoken to so far.

“The chinese mistress of one of the officers pleaded for my father to be released, saving him from torture.”

Victor Amaloo from Ipoh

Our family was living in No.3 Sungei Pari Road house in Ipoh,Perak. The most frightening day was when the Japanese planes bombed the goods shed at the rail yard, where the retreating British forces were loading their ammunition, gasoline drums, tanks and military vehicles into freight and open flat rail cars to go south to Singapore. The result was a continuous bomb explosion with bomb sharpenel flying around. The debris from the military vehicles with exploding bomb air pressure sprayed many miles with burning oil and metal parts.

We gathered whatever we could and started running along the road to go further away from Silibin. We had escaped to Jalapan which was many miles away. I was carrying my one-year-old sister. It was so frightening to be pushed down by the air pressure of each bomb blast which was so strong.

However what was dangerous to say the least and what all of us could not bear at the same time was the fact that at every bomb blast, hot burning oil droplets fell on us together with the air pressure that knocked us off our feet.

One day, the Japanese planes sounded quite close and all the people ran to the nearby banana plantation for cover as there were no air raid shelters for protection. Then all of a sudden we heard a loud bomb blast and all of us sat shivering with fear when I heard a splash sound. I looked towards the sound and was petrified with horror when I saw a woman’s decapitated body falling to the side owing to a bomb shrapnel. She had been holding a child in a sitting position. Her body was wriggling with her arms still holding the child!

With the Japanese occupation in 1942 all school-going children were asked to go to school and study the Japanese language. As such, my 2 elder brothers and I had to attend the Japanese School which was at the Convent School for girls before the war. One day, we saw three men digging a trench and some Japanese soldiers standing nearby, controlling the crowd. The trench was not deep. Suddenly the Japanese soldiers called all the people to stand at attention and bow towards a car that was approaching. When it stopped, a Japanese General with a long sword at his side got out and came towards the three men who had stopped digging. He waited until the Japanese soldiers tied the 3 men’s hands behind their backs, blindfolded them with a black cloth and made them kneel in front of the trench. Then the General took his long sword out, raised it high above the 3 men and with a bellowing roar, beheaded them one by one. As the sword slashed their necks, he kicked their decapitated bodies into the trench while their heads went rolling on the grass. Then the soldiers took their heads, stuck them onto the top of bamboo poles and asked the people to follow them. They then planted the poles at the corners of the General market. A cardboard written in Japanese characters warned people to see what would happen if anyone was anti-Japanese (collaborators for the British). The heads were there for a few weeks turning black before they were removed. All the people were shocked, dumbfounded and scared to death.

There was a shortage of every basic commodity like rice, bread, sugar, salt, spices, fish, meat (pork, beef, mutton, poultry), vegetables and even clothing as all these first went to the Japanese military. The people were given ration cards for fish and meat only. Those who worked for the Japanese were given three “gantangs”, which is a few kilos of rice and three “katis” around (3.9 lbs or 2 kilos) of dried salted fish each month. The salary for workers was very small and people were paid with Japanese printed currency as the previous Malayan British currency was not valid anymore. Dad with seven children found it difficult to support the family.

Owing to dire living conditions, Dad also asked me to get a job so I too could get some rice and dry fish for the family. I had to quit school and by then I was able to speak and write in Katakana, Hiragana and a bit of Kanji which was like Chinese characters but in Japanese. The military section at the Ipoh Railway Station had an opening for an Indian as a translator and other duties. I went for an interview with the Japanese chief and I was then employed at the Railway Transport Office at their Military section.

The Japanese at that time were constructing a bridge to connect Thailand and Burma for their troops and this came to be known later as the Burma Death Railway. Hundreds of thousands of military prisoners of war and local men died in the construction of this railway and bridge project.

The Japanese wanted more workers for the railway project and devised a clever plan whereby they informed the public in Ipoh that Toddy (a fermented coconut water which had an alcoholic effect) would be given free for three days to all those who came by the toddy shop near Silibin. As a result there was a huge crowd of men on the third day. All of a sudden the place was surrounded by the Japanese who interned all the men (mostly Tamil speaking Indians) who were not employed by the Japanese. They loaded the men in their trucks and were deported for the construction of the railway bridge in Thailand. That very night I was on night duty and the men were put in covered goods train, all cramped with not much space to move. Some of the men’s wives pleaded to set them free, crying. I took a great risk to help some escape. Just before the train left, I selected a few and told them to get off the train while telling others in the goods train that I am giving the selected men a food pass for all of the men when the train arrived in Prai. I took them to the end of the railway station and told them to escape.

One day when I went to work in the day shift, I saw two men in a man-hole at the Railway Station. The drain water was flowing over their heads and I was told they were put in there by the Japanese for coming close to the entrance of the kitchen area. The man-hole cover had 1 inch-spaced iron rods and people could see the men squatting and soaking wet and shivering with the filthy water pouring over them. They were there for a few days and one day, I did not see them anymore and nobody knew what had happened nor of their fate.

On 15th August 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies after atomic bombs were dropped by Americans on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I quickly went to the Railway Station and stopped short of going near the office as the Japanese were firing their guns at the ceiling in disgust and shame. Nobody ventured out and most of the people stayed indoors as the Chinese Communists took reprisal on whoever they found had sided and helped the Japanese.

A few days after the arrival of the British, they rounded up all Japanese troops in their camps, made them prisoners of war and made them give up all their armaments. The Japanese prisoners were then marched by the British soldiers to a prison camp. When the news spread of the intended Japanese prisoners-march in Ipoh, I ran to see it.

While the prisoners were being led to the prison camp, some people broke the lines and slapped the Japanese in retaliation to vent their anger but the British soldiers prevented the assault. Till today I cannot forget it and I can picture the face of my Japanese boss who saw me and turned his head to the other side in humiliation.

Victor now resides in the USA.

Victor Amaloo

During the post-war days, there were still acute shortages of food and essential items. The vendors did not accept the Japanese currency, which became worthless overnight.

Chan Peng Fook

In Peng Fook’s memoirs (sent to us by his granddaughter Sweet Ling), he remembers having to study Japanese at school, which later enabled him to join a Japanese company, which paid him with rice rations – a big incentive during the war.

In the mornings, the employees would have to do “taiso” – physical exercises and oath-taking to swear loyalty to the company. His Japanese bosses were kind, and even bought instruments so the staff could form a band.

When a local colleague was slapped by a Japanese officer, his boss went to see the commander, who had the officer reprimanded. When a female relative of Peng Fook’s was abducted by the Japanese to be used as a comfort woman, her husband’s Japanese boss helped obtain her release.

There was times he assisted in distributing rice to the company staff, and he used to give out more rice than allowed – a risky move. Besides that, there were frequent recruitment drives for young men to join Japanese organisations. He and a friend went, but withdrew on the advice of their elders.

The town amusement park was opened nightly to provide relaxation for locals, and in KL, the BB Cabaret was opened and provided female dance partners.

He was caught in the midst of Japanese bombing of Klang Town Centre, and managed to survived unscathed but suffered shell shock.

One night in January 1942 there was the sound of canons firing at Meru, north of Klang, where some fighting took place. He later learnt Japanese soldiers had bayonetted Gurkha prisoners tied to rubber trees to death.At night there was a long convoy of Japanese trucks moving south in pursuit of the British. Later in the night marauding Japanese soldiers entered Chinese homes to look for valuables and women.

One night he turned on the radio and listened to the ‘Double Ten 10 October’ Voice of America broadcast. Suddenly a Japanese soldier appeared at the house drawn by the radio noise and made a room to room search. But he missed Peng Fook’s room even though he passed it twice. The Japanese military punishment for listening to the radio was death by beheading.

Wong Chee Keong

Submmited by his granddaughter Wye Yi, the late Chee Keong was a photographer in Seremban during the war – an occupation which later helped saved his life. When the Japanese took over Malaya, they ordered that every photo that was sent to be developed be submitted for censorship by the Japanese authorities before the photo studios were allowed to give the processed photos to their customers. He was also among those who were put into Japanese language classes and did very well in the language school.

How did this save his life? One day, Japanese soldiers came into the part of Seremban that he was in. They ordered that all the men line up in the middle of the street. Nobody knew what was happening and they were kept standing there for 2 hours.

Suddenly, a Japanese Kempetai, Akai-San called out to Chee Keong, “Photographer! what are you doing there? Go home!” He had interacted with Akai-San before because of the photos he had to deliver for inspection every day. This encounter saved his life, because later on, all the young men from that day were never heard of again.

Eventually, he was forced to work as a medical aide in an army camp in Port Dickson, where he formed a lifelong friendship with another Malayan, Ismail Budaya. The friendship between their families continues today. The late Chee Keong also formed the Camera Club in Negeri Sembilan.

Lee Soo

Lee Soo, 95, was living in Batu Talam, Raub, Pahang when the Japanese invaded. With a family of 7 to support, he had to work as a black market trader. Once, as punishment for disturbing the peace, the Japanese chopped off the heads of 4 villagers who had gotten into an argument. The heads were later hung at the corners of the town as a threat to the villagers.

He also remembers how his former headmaster was forced to become a farmer, and when he saw him again two years later, the headmaster’s body was skinny and covered in scabs. Lee Soo felt sorry for him and gave him a bag of millet, and the ex-headmaster was so grateful he fell to his knees.

Abdul Manaf B. Busu

Submitted by his granddaughter, Al Aaina: Abdul, 94, was a small boy living in Lubuk Cina, Negeri Sembilan, when he heard from the other villagers that the Japanese were making their way through Malaysia to get to Singapore.

He heard that the British wanted to set up bombs to destroy bridges, to slow down the Japanese advance, so he and his friends helped set up a bomb to be placed on the Linggi bridge. They pulled the bomb cables to the bridge, and took cover before the British blew the bridge up.

Abdul and his friends wanted to follow the British to Singapore, to fight the Japanese, but eventually stayed in Negeri Sembilan.

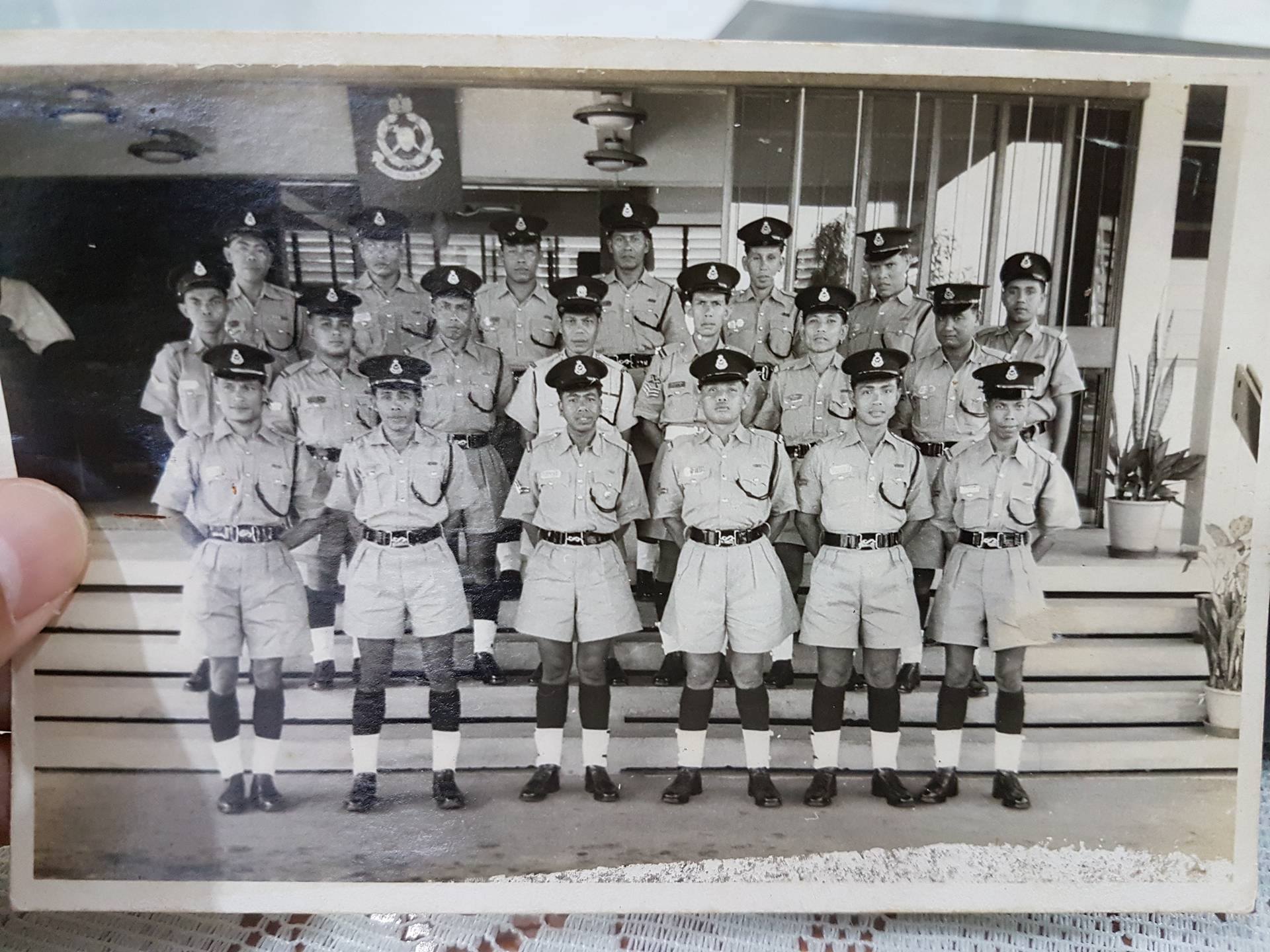

He remembers only 4 – 5 people surviving the explosion. After the war, Abdul became a police officer, working in Butterworth, Teluk Tawar, Brunei and Ipoh, until he retired in 1992.

(Front row, far right) Abdul Manaf served as a police officer after the war ended.

Reader’s gallery

Pictures contributed by readers. Email us your photographs now at alltherage@thestar.com.my

Readers of The Last Survivors send in World War 2 pictures of Malaya. To contribute stories, videos, or pictures to The...

Posted by R.AGE on Monday, March 21, 2016

Leave a reply