Video by HAFRIZ IQBAL, HANSEL KHOO and CHEN YIH WEN

Story by CLARISSA SAY and HAFRIZ IQBAL

“PEOPLE laugh at me these days,” said Charles Zico. “They say I used to be a field operator for a big oil and gas company. Now look what I’m doing.”

Like many young people in Miri, Sarawak, Zico found himself without a job after global oil prices came crashing down last year. And as the sole breadwinner of his young family, he had no choice but to take up a job working with dangerous pesticides, for just a fraction of what he was earning before.

He said he used to earn RM6,000 a month. Now he gets around a quarter of that.

I had to explain to my children why we can’t afford the things we used to have,” said Zico with a sad smile. “And that if they really want it, they’d have to wait for their grandparents to visit.”

Zico earned around RM6,000 when he was working in the oil and gas industry. Now, he does pest control, for about a quarter of his old salary.

Miri is a city built on oil. Not so long ago, those arriving at Miri Airport would find it full of oil workers in brightly coloured overalls, travelling to or from offshore oil rigs. When the R.AGE documentary crew went there a few months ago, it was almost deserted.

Ardiles anak Roland, 25, was one of those oil workers.

He used to bring in a hefty paycheck working as a cook on an offshore tanker. Today, he waits tables at a hotel.

“When I was with the oil and gas industry, I felt great,” he said. “I had enough money to socialise and go drinking with friends, and I spent most of the money I earned.”

Ardiles had been at his job for about a year when he received news of his retrenchment. It was a huge reality check for him.

He had only just graduated from college and had a student loan to pay off. He had a car loan, and almost zero savings.

“Young people are getting retrenched more, especially in the oil and gas sector where big companies are facing major profit losses and need to restructure and resize,” said Shamsuddin Bardan, executive director of the Malaysian Employers Federation.

And when most companies retrench, they usually do it on a “last in, first out” basis, meaning young people are often the first out the door as they’re last ones to enter the company, explained Shamsuddin.

That’s a huge problem for young people in Miri, where many grow up taking a job in the industry for granted.

The Grand Old Lady is Malaysia’s first oil rig. Today, it no longer works – just like many of the young people in Miri since oil prices crashed in 2014.

Plan B

So what do you do when the one skillset you’ve spent years acquiring suddenly becomes redundant?

Harry Leong, 24, was an oil and gas technician before he got retrenched by oil exploration company Schlumberger. He worked hard, having gone an entire year without taking a day off.

At the end of that marathon year, he was retrenched.

There was a silver lining of sorts for Leong, who said he felt relieved to finally have some time off. “It’s weird but I was secretly happy,” he said. “It had been a long time since I felt the joy of holiday.”

But the holiday mood faded quickly when he realised he couldn’t afford his car and housing loans anymore.

When rumours began floating around of possible layoffs, Leong said he and his colleagues weren’t too bothered.

“This was three months before the retrenchments started,” he said. “We thought we were safe, that there was a small chance it would happen to us, so we ignored everything.”

By the time they began to take the matter seriously, it was too late. Leong and many young colleagues were on the chopping board.

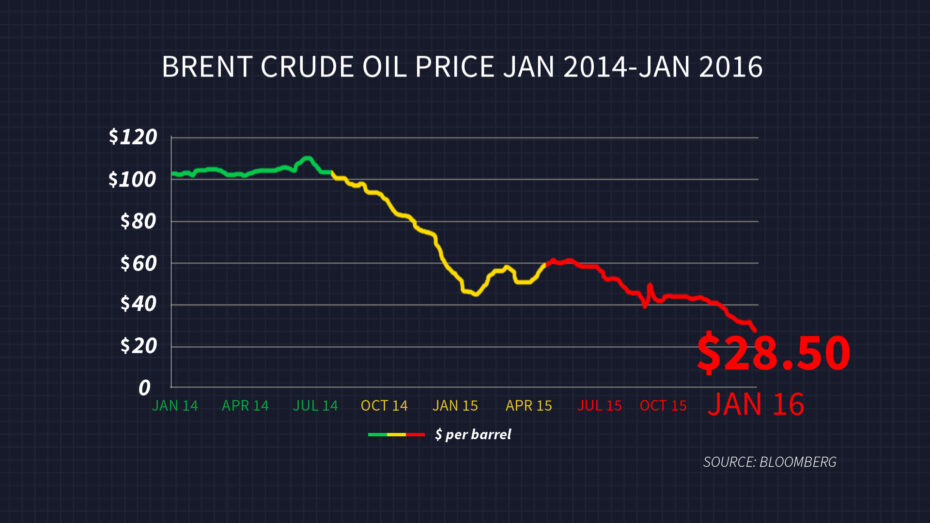

Here’s what happened in a nutshell: in 2014, the United States found itself with more oil than it could possibly need as smaller companies began pulling oil out of shale, a type of oil-rich sedimentary rock, instead of drilling for it the traditional way.

And while shale oil isn’t anything new (it’s been a known source of oil since 1985), the technology used to extract it – known as fracking – still is. Today’s fracking technology means that it takes a lot less time, effort, and money to pull oil and gas out of shale.

To keep its market share, Saudi Arabia led the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to flood the market with more oil from the Middle East.

They were hoping the lower prices would drive the US out of the game. But then Iranian oil became available after economic sanctions were lifted, and the oversupply drove oil prices to the lowest in recent history. That was a year ago.

Global oil prices plummeted due to an oversupply of oil in 2014. It forced many oil and gas companies to downsize, which had huge implications for cities Miri, where so much of the local economy is based around the industry.

Consumers rejoiced, but oil and gas workers like Ardiles and Leong had to take the hit.

Oil and gas workers, although standing on the frontlines of this economic drop, weren’t the only ones affected. Last year saw a jump in Sarawak’s unemployment rates, from 3.1% to 3.5%. To put things in context, that’s 43,500 unemployed people in the state alone.

So what do you do when the one skillset you’ve spent years acquiring suddenly becomes redundant? Ardiles said most of his ex-colleagues had no choice but to switch industries altogether.

But because not all of them could afford to learn and master another hard skill, they were forced to do manual labour. It created a lot of disillusionment, but it was the only way to put food on the table.

“One guy I know is now working in a farm,” said Ardiles. “I have another friend who has been unemployed for a while. I keep asking him to join me where I work because he has a wife and child to provide for.”

Ardiles went through the same dilemma himself – to work for what seemed a pittance, or not work at all.

He now works at the Pullman Hotel as a banquet server. It doesn’t carry the same prestige as his old job, but it puts food on the table, and that’s what matters to him at the moment.

Ardiles now works as a banquet server for a hotel. He said some of his friends who were retrenched cant bring themselves to do such menial work.

The big picture

How this affects all of Malaysia is a case of simple economics. According to the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA), the oil and gas industry currently contributes 20% to Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP).

And until 2014, about a third of government revenue came from local oil and gas giant Petronas. Those are huge contributions, considering they come from a single sector.

Shockwaves from the oil price plummet spilled over into other industries. 2015 saw the highest number of retrenchments in the past six years with 28,499 Malaysians from various sectors being let go.

“This is the danger of making a particular place very dependent on one industry. If that industry is not prospering, then the whole place will be in ruins,” said Wan Saiful Wan Jan, chief executive of the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs.

“Of course, the dependency on the oil and gas industry as a whole needs to be reduced and the government realises this. It has been reducing those figures over the years,” he said, adding that the government should diversify their sources of revenue.

“They just stopped calling back,” he said. “One second I had work, the next second I didn’t.”

For undergraduates in Miri who will be entering the job market soon, this brings up an important question: what now?

Kamarul Ariffin’s father worked in oil and gas, but he’s having second thoughts about joining the industry now.

“My dad used to work offshore, but now he’s just an office boy,” said the 19-year-old. “That’s why I’m thinking about going into IT instead.”

Hamizan Muhammad, 20, isn’t sure what to do. He recently applied to study safety management in university so he could work offshore, but now hopes his application is rejected so he can choose another course.

“If I don’t get a placement in that course, I will consider something else, like business management,” he said.

Things have improved slightly in the past few months. The Wall Street Journal reported a 0.3% increase in the FTSE Bursa Malaysia stock market index last week, thanks to an overnight rebound in oil prices. Still, it’s hard to tell if Miri is on the road to recovery.

One thing’s for sure though – Miri-ans know how to tough it out.

With no job prospects on the horizon, Leong decided to further his studies in Mechanical Engineering so he’d be prepared when the market becomes stable.

“I already have the work experience,” he told us, “But because of the current economy, I’ll need more if I want to find a good job.”

Mccolin and his father, back when they were both in the oil and gas industry. As a young person, McColin was retrenched, but his father was able to keep his job.

For Mccollin Ferguson Philip, 22, getting burnt once was enough.

He used to get paid on a project basis, and one day, the projects just dried up. Shortly after that, he lost his job altogether.

“They just stopped calling back,” he said. “One second I had work, the next second I didn’t.”

Unfazed, Philip took the opportunity to explore his interests and started working as a tattoo artist to make ends meet. Tattooing is now his passion, and he has left the oil and gas world behind for good.

“After being treated like that, I couldn’t stay on in that industry. Tattooing is my career now. I have a keen interest in it and I’m confident it can support me.”

Despite not being able to afford a second degree, Ardiles isn’t giving in to his fate either. Although he doesn’t know what his next step will be, he doesn’t see himself waiting tables forever.

“It doesn’t matter if the job is in oil and gas or not, as long as it’s a permanent job with a decent salary. I just want to be able to take care of myself, my family, and my future wife and kids.”

Leave a reply