FOR Ineza Roussille, there had never been any reason to ask her grandmother, former first lady Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, about the Japanese Occupation, which started almost 75 years ago on Dec 8, 1941.

While she had heard her grandparents talk about it, she never dug deeper until the filming of season two of The Last Survivors, an interactive documentary by R.AGE.

In the video, launched today at fb.com/LastSurvivorsMalaysia, Siti Hasmah retold stories from the war, and how she managed to find glimpses of humanity among the horrors of the time.

Siti Hasmah’s video will be followed by two more episodes, featuring a Death Railway worker who volunteered himself into service to search for his brother, and a prisoner of war (POW) who managed to survive the cruelty and deprivations of a prison camp in Japan.

Filmmaker Roussille said it was the first time she’d revisited her grandmother’s old haunts, and also the first time she’d heard the whole story.

Roussille, 29, was fascinated by her grandmother’s tales, many of which she had never heard before.

“As a family, I don’t think we have ever sat down and talked about it. It was fascinating hearing her stories and I learnt so many things about her,” said the filmmaker.

Rousille had the opportunity to visit the sites that figured prominently in her grandmother’s history, like the Masjid Jamek Alam Shah mosque in Pudu, which still stands today.

“I didn’t know where she lived, so it was interesting driving around as it’s a corner of KL that I’ve never visited. I was a bit sad for her, not being able to see her house again after more than 50 years,” she said.

“Listening to her stories gave me a different perspective of the war, and really brought home the point that conflict affects us all.”

Survivors’ stories

Unlike Roussille, Aruna Irani Santhiran, 24, has heard her grandfather’s stories many times.

“My family and I have been listening to the stories for as long as I can remember, and the war in Malaya has become something important to me,” said Aruna.

Aruna’s grandfather, Arumugam Kandasamy, 90, was a survivor of the Death Railway, one of the few from his hometown of Linggi, Negeri Sembilan, who returned from the railway project alive. He started work there when he was 14.

Arumugam’s fluency in Japanese – which he taught himself – saved his life by enabling him to get a job as a translator while working on the Death Railway.

“I know from his stories that out of the 50 men taken from Linggi, only seven returned, and he was one of them,” said Aruna, who currently works as a nurse in Linggi.

Over 75,000 Malayans, many of them Indian, were forcefully recruited to work on the infamous Death Railway which ran from Thailand to Myanmar. An estimated 42,000 workers perished from a combination of back-breaking labour, poor conditions and ill treatment by the Japanese.

Despite so many Malaysian Indians having lost relatives to the Death Railway, many of them don’t know – or care to know – much about their own ties to history, said Aruna.

“Their grandparents may have died on the Death Railway. They were an important part of our past, and we should learn more about their history,” she said.

The lack of emphasis on World War II and its impact on Malaya in school textbooks meant students like Francine Yeap didn’t really relate to the war, but instead saw it as information and dates she needed to memorise for her exams.

However, her own grandfather, Lim Chung Bee, 93, had harrowing memories of the war.

As one of the few Malayan POWs in Japan, Lim, then only 17, found himself in a prison camp, labouring in a dam. Many of his cohorts died, but Lim managed to come home and raise a family.

Today, dementia makes it difficult for him to share tales of his past, but he has managed to relate some stories in bits and pieces. His grandchildren have filled in the blanks by poring over his old photographs and a diary he kept during the war.

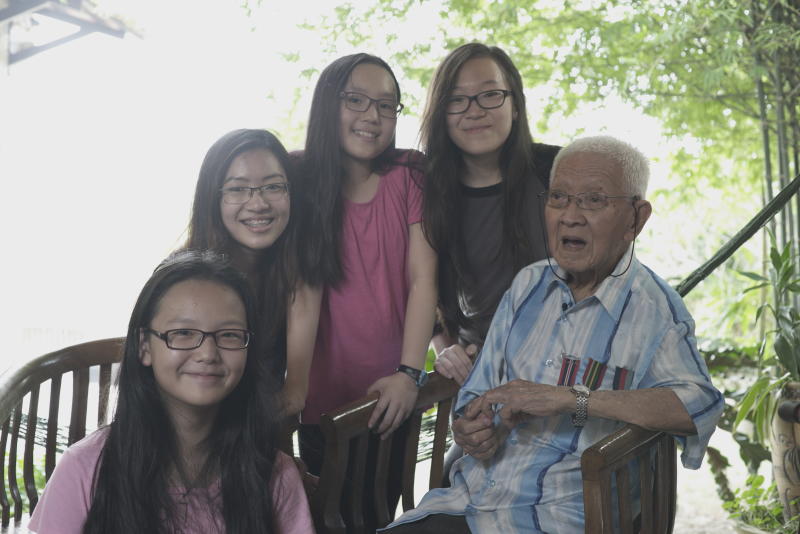

Lim (bottom right) was 17 when he was captured by the Japanese. Today, his dementia means most of his memories are gone, but his photos and wartime diary, thankfully, remain.

“When I was younger he’d talk about the war and his experience – he has three bullet wounds. He liked to talk about it but now because of dementia and my schedule, it’s hard to really sit down and listen,” said Yeap, 20.

Yeap and her younger sister Amber were so inspired by what they had learnt through their grandfather’s history, they decided to showcase Lim’s story at their church youth group.

“I used to dislike history because it was like ‘we’re learning about dead people, what’s so great about that?’ I think everyone our age has the same sort of mentality,” said Amber, 16.

Amber was so invested in learning as much as possible about her grandfather, she devised a way to jog his memory during the filming. She made flash cards with enlarged keywords for Lim to look at, which helped a lot.

“I realised he could see the words on my mum’s phone and thought, if his eyesight is better than his hearing, why not?”

Now, the sisters have started sharing more historical films, in an attempt to foster a love for history among their peers.

“Amber’s classmates weren’t interested in history even though she is, so we also showed the movie Unbroken to our youth group and that really got them thinking about how we can learn from the past – I think it’s good exposure for our generation,” said Yeap, an English and Public Relations student.

Learn from history

Seventy five years on, it’s easy to forget and ignore the struggles Malayans went through during the Japanese Occupation. However, both the survivors and youth are adamant people remember and learn from it.

“The Death Railway wasn’t something where a handful of people died. Thousands died, many of them Tamilian,” said Arumugam, whose brother was among those who perished.

Aruna has made it her mission to share her grandfather’s story.

“Not everyone is fortunate to receive the information firsthand. I also think it’s important that Malaysians recognise what the previous generations sacrificed for this country, especially the minorities,” she said.

Roussille spoke of the importance of understanding yourself through your family history and origins.

“We need to learn from the progress – and setbacks – we’ve made and faced, so we don’t make the same mistakes again,” agreed Roussille.

“And it’s not just your family history, but also the history of your city and country, because it shapes who and how we are today.”

Lim granddaughters (from left) Azelynna Lim, Francine, Kyra Yeap and Amber, pored over his diary to learn more about him. Francine and Amber also shared his story with their youth group to spark an interest in history.

From her grandfather’s accounts and his wartime diary, Yeap realised the gravity of war and urged other young Malaysians not to take peace for granted.

“Just because we’re privileged to live in a time of peace doesn’t mean we should forget about the past and the struggles our grandparents lived through,” said Yeap.

Leave a reply