By LIM MAY LEE

fb.com/thestarRAGE

The night before Malaysia’s historic 14th General Elections, at 10pm local time, there was a face-off of sorts. The incumbent Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak and his challenger and former mentor Tun Mahathir Mohamad both made their final appeal to the Malaysian public.

Perhaps there was no starker comparison of these two candidates. Mahathir’s speech was streamed live on Facebook only. Najib’s was streamed online and broadcast over mainstream TV channels.

Mahathir’s stream was raw, delivered on a stage like any other ceramah stage. Najib’s broadcast was polished, performed in front of his family home in Pekan, Pahang. The home was lit up like a set piece, in Barisan Nasional (BN) blue.

The online campaign machinery for both sides was in overdrive. Over the course of the day, Pakatan Harapan (PH) shared six posts on its official Facebook page. BN shared 27.

While PH’s posts were simple – two calls to vote, a campaign video, information about bus services and, of course, Mahathir’s speech. BN’s posts announced perks, slammed political opponents, disputed “fake news”, listed all the subsidies the BN government had provided over the years, and managed to squeeze nine videos into a 24-hour period.

Two vastly different candidates, two vastly different campaigns.

We all know what happened the next day.

But that night was the tail end of a long, fraught social media campaign waged by both sides. Malaysia is widely known to be one of the biggest Facebook markets in the world. 22 million out of Malaysia’s 35 million population are on social media. 88% of the population aged 25-34 access the internet on a daily basis.

So it’s no surprise that the battle for the hearts and minds of Malaysian voters would be played out on the internet. Twitterbots were allegedly hired. Viral videos were created and disseminated ad nauseum. Millions of ringgit were reportedly spent on Facebook marketing alone.

All to woo voters like Adi.

Adi Izzudeen Annuar, 23, was a first-time voter. He was one of an estimated 1.6 million new voters analysts considered political wildcards because they were seemingly apathetic and fence-sitting.

But they weren’t – they were studying the options.

“I get almost all of my news from social media,” said Adi. “With mainstream media being monopolised, it was the only platform where I could see what both sides of the divide had to say.”

Without a clear allegiance, these new voters represented a key electoral battleground.

But while it was difficult to keep tabs on them and who they supported, young, tech-savvy Malaysians like Adi had no such trouble keeping tabs on their political parties, thanks to social media and the Internet.

And from what Adi saw on social media, he wasn’t impressed.

“I voted for a change in governance,” said Adi. “Using social media to track both parties, it was clear to me that in order for the country to gain true democracy, there needed to be a change.”

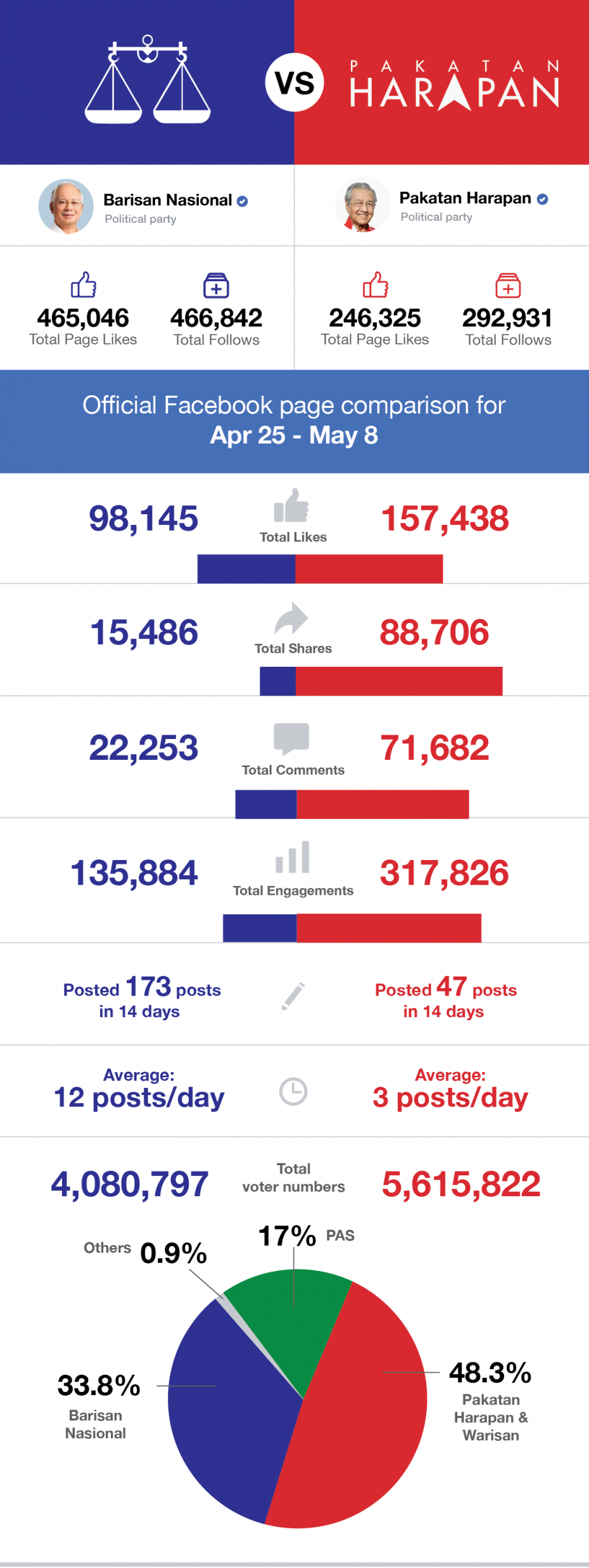

22 million out of Malaysia’s 35 million population are on social media, making Malaysia one of the biggest Facebook markets in the world. Unsurprisingly, the battle for the hearts and minds of Malaysian voters was played out online. The night before GE14, both prime minister candidates livestreamed their speeches in a last-ditch attempt to sway voters. As the numbers show, PH won the social media battle. Offline, we all know what happened. The question now is: “How?” The answer, experts say, could lie in digital marketing.

Campaign war

“Our strategy was to target fence-sitters using big data,” said Naim Brundage, Chief Marketing Officer of Invoke Malaysia. Invoke Malaysia is the digital marketing agency that managed the social media accounts of 103 Pakatan Harapan candidates during the elections.

According to Invoke, they have over a million different data sets accumulated over the space of a year through voter rolls, online and offline surveys, NGO and political memberships, as well as data mined from social media.

But that’s not all – even the content they created was based on big data.

“We ran surveys to find out what people wanted to talk about – whether it was 1MDB, GST, or even luxury handbags. We would pick our topics based on those responses, and it allowed us to run very targeted campaigns,” said Naim.

Invoke spent RM800,000 on Facebook marketing. Its BN counterparts declined to reveal their spending.

In contrast to Pakatan’s streamlined, data-driven strategy, BN allowed each branch and candidate to run their own social media accounts. The messaging differed sharply, too.

While PH’s data-driven messaging which was based on what the people wanted to discuss, BN’s messages were more top-down.

“Our social media campaign was about letting Malaysian youth know what’s at stake,” said former Umno deputy youth chief Senator Khairul Azwan Harun. “We showed the youths how we envisioned Malaysia as compared to what the (then) opposition had planned.”

“This is what we presented on social media, responsibility and stability. But I guess it was not spontaneous enough. It was hard to make stability and economic sense a sexy catchphrase.”

Unfortunately, by the time BN got aboard the social media train, their message may not have even mattered anymore.

“The biggest mistake I noticed in terms of BN’s social media campaigns was that they only started about two months before elections,” said Naim. “By the time they tried to reach the voters, they had already been exposed to our messaging for almost a year. It was too late.”

On top of that, their messaging and visuals didn’t really help, he said.

“They were sending pictures of Najib, clean-cut and dressed in a suit, to rural areas where people couldn’t afford suits,” said Naim.

This form of untargeted messaging, coupled with allegations of the former Prime Minister’s mismanagement of funds, and Tun Mahathir’s undeniable popularity, may have played a part in alienating the Malay base BN had been counting on.

“Even the Malay voters, who traditionally vote BN, were unhappy. This caused the votes to split quite badly between PH and PAS,” said political analyst Ibrahim Suffian. “Even though they may not have trusted Tun Mahathir initially, they ended up giving some of their votes to him. The rest, who voted conservatively, went to PAS.”

By the time May 9 rolled around, BN’s social media campaign was lagging far behind.

The problem with BN’s marketing strategies, said branding consultant Marcus Osborne, is that it followed their previously tried-and-tested methods of broadcasting messages.

“They were pushing the same type of messages that used to work when the country had maybe two TV stations and no non-mainstream media, but (they pushed it) on social media,” said Osborne.

“While PH was engaging with people, BN was talking at them instead of to them, and people noticed.”

It didn’t help that the mood on the ground was dark, something experts agree BN would have picked up on if it had engaged with its audience.

“There was a lot of anger. Compounded with the fact that BN’s legitimacy had been chipped away by all the scandals and the rising cost of living, it’s not surprising that people felt like it was time for a change,” said Keith Leong, head of research at public affairs consulting firm KRA Group.

This anger made it even more difficult for BN to sway voters back to its side.

Even before the first vote was cast, the verdict was already out. Pakatan had won the online war. On that final day before elections, as both prime minister candidates made their final plea to voters, the numbers on both parties’ official Facebook pages told the story.

BN’s 27 posts garnered almost 13,000 likes and shares: PH’s six posts received almost 200,000.

A tech tsunami

“Technology created a level playing field, information-wise,” said Ibrahim. “It enabled people to get information on a minute-by-minute basis, and more importantly, mobilised people to vote.” It was revolution by social media.

And the internet didn’t just mobilise people to vote, it literally mobilised votes.

Vote runner Ravi Rishyakaran, 35, can attest to that.

A chance click on a Facebook link led him to a GE14 postal voters’ Facebook group, where he realised hundreds of Malaysians worldwide were struggling to get their postal votes back in time.

There, Ravi found a post that resonated with him. It was from a Malaysian living in Japan, who needed help getting postal votes back to Petaling Jaya. A Japanese man would be carrying his ballot back on a flight on the day of the polls, and Ravi agreed to pick it up from the airport and rush it to its designated polling station. And with time to spare to cast his own vote.

He intended to do one favour, but ended up being part of a global network of vote runners, all helping other voters to get their postal votes back in time.

“My inboxes were blowing up! They were messaging me on Facebook and WhatsApp, even via SMS!” he said. “It was really amazing to see how social media brought all of us together.”

While it’s impossible to track exactly how many postal votes made it back because of Ravi and the other vote runners, EC stats show that there are almost 8,000 Malaysian postal voters living abroad.

“I honestly don’t know how many votes we managed to deliver, but it felt like thousands,” Ravi said.

“KLIA 1 and 2 looked like civil post offices – people were dropping envelopes off, others were separating them, and people like me were running to counting stations – it just felt amazing that one click on Facebook led to this.”

But they weren’t the only ones using technology to mobilise votes.

When it was announced that GE14 was going to be held on a weekday, people were outraged. Not only was it in the middle of a working week, many would also have to spend time and money traveling back to their home states.

To help those struggling with travel arrangements, a group of young Malaysians set up PulangMengundi.com, a website that connected them with people who were willing to carpool or sponsor travel costs.

“A bunch of friends and I were so incensed at this travesty, we bought the domain name and co-founded the platform,” said Andrew Loh.

They worked remotely – Loh works in the Middle East – and around their existing day jobs, funding the website out of their own pockets.

By the time May 9 ended, they had connected over 10,000 people and helped collect over RM100,000 in subsidies for those who needed funds to go home.

“It’s clear the people were very invested in ensuring democratic processes were followed. They monitored the situation closely online, and rallied their peers. Simply put, it was a tech revolution,” said Leong.

That revolution helped make history. BN is now the opposition for the first time in 61 years.

Open to abuse

However, like all tools, social media can be abused.

“While it’s great that everyone is connected and informed of national issues, this also means that a lot of us can become misinformed very quickly too,” said Azwan, who now sits on the Senate.

“The greatest abuse (of social media) comes when we start spreading false information, especially ones that may be defaming others. To curb this, we need to popularise a culture of fact-checking, a habit of checking for sources.”

Leong agreed with the necessity of staying vigilant.

“This time, it was used for fairly benign purposes, but people need to be savvy when they find news online,” he said. “It’s unnecessary to have a fake news bill because it’s impossible to legislate common sense, but we should have regulations and increased media literacy. People need to really evaluate the information they’re sharing and receiving.”

That’s what Adi plans to do. Over the next five years, he plans to continue using social media to stay up to date on government activity, carefully checking both sides of the political divide each time.

One more tool he could use is The Harapan Tracker (harapantracker.polimeter.org) – a non-partisan website that tracks government performance in order to hold them accountable for their promises.

“I’ll be keeping tabs on the new government,” he said. “While I voted for Pakatan this time, I believe for a country to achieve a healthy democracy, there should be at least two changes of leadership – and come GE15, I will be voting for the best party, whoever it may be.”

Tell us what you think!