By ELROI YEE

alltherage@thestar.com.my

Somewhere in Kapar, Klang, around the corner of an ordinary residential area, past neat rows of terrace houses and a nondescript block of shop lots, the street narrows into an alley, which then crumbles into a pothole-ridden dirt path. A short distance down that dirt path, stands Mariyammah’s home. It is perched just beyond the glow of streetlights, and beyond the reach of the electricity grid and water supply pipes. There is electricity at the home, but the family does not pay for it, and water is hauled by the bucket every day from a nearby tap.

The house is made of wood and zinc, built by her husband from scratch some 20 years ago on a vacant plot of land. Since then, it has seen the birth of seven children, its dimensions expanding together with the family as new rooms are built around the original structure.

But as much as the house has changed, it can hardly be said to have kept pace with the surrounding district of Kapar. What used to be a plantation community is now a suburban town that houses a largely middle class population. 20 years of progress has brought economic opportunities and education. A large Chinese school, with multi-story blocks of classrooms and a large banquet hall, stands a short walk away from Mariyammah’s home. Businesses are aplenty. Factories provide jobs. It is still a far cry from Bangsar or Mont Kiara or Damansara, but there is little visible evidence of poverty.

On the fringes of an ordinary residential area, a dirt path leads to a squatter community, where Mariyammah’s family lives. ― Photos by: ELROI YEE/The Star

Unless you walk the short distance down that dirt path. Every morning at eight, Mariyammah takes that dirt path out of her squatter neighbourhood to a factory in Klang, where she works a minimum-wage job. For many years, she was the sole breadwinner of the family, until two of her daughters recently started working. She prefers not to talk of her husband. The family’s income salary is not enough to survive on, and they only get by through monthly provisions donated by a local NGO working among the urban poor in Kapar.

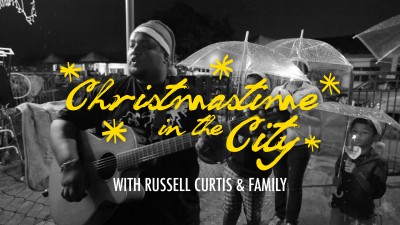

In spite of this, we never once heard a complaint from her or her children over the three visits we paid to the family. During the last of those visits, we asked local band Jumero to surprise them with some Christmas carols. They invited two powerhouse singers, Joy Victor and Evelyn Feroza, to join them. The carollers were all impressed by Mariyammah’s determination to stay positive. Only once did Mariyammah express dissatisfaction ― when she described how her youngest son was expelled from school: “Tak ada warning apa-apa, terus buang.”

The bedroom where Mariyammah and her daughters sleep. Their home is basic, but to them it is home nonetheless.

Kanages is 15, and was studying at SMK Tengku Idris Shah. Apparently, he was expelled for breaking a chair. In an effort to put her son back in school, Mariyammah missed a day of work (and forfeited a day’s wages) to meet the school authorities. “Saya cakap saya boleh bayar untuk kerusi itu, tapi tak boleh. Buang juga.” As it stands, Kanages, a bright-eyed boy with a winning smile, will no longer go to school. He currently works odd jobs at construction sites.

Jumero, Victor and Feroza joined forces to spread Christmas cheer to Mariyammah’s family by singing carols and spending time with the children.

At the factory, Mariyammah forms part of a production line that makes decorative lights ― the kind of lights strung around Christmas trees. The first time we met her at her home, it was nighttime and we noticed the ranks of chasing bulbs draped along the walls and hanging from the ceiling. “Saya beli dari kilang ada murah sikit,” she tells. At this point, the children laugh sheepishly. Mariyammah explains that the lights are for her children, who wanted to celebrate occasions such as Deepavali with some semblance of festivities. So she bought the lights, and the children put them up.

The bedroom of Mariyammah’s youngest son, Kanages. Expelled from school without warning, he is now doing odd jobs at construction sites. He hopes to be allowed back to school when the new school term begins in January.

We ask if she has a wish for Christmas this year. “Bagi saya sendiri, tak ada,” she replies after some prodding. “Hanya mau anak saya semua gembira, semua baik-baik, itu sudah cukup. Saya sendiri susah tak apa, tapi mereka mesti baik-baik.”

Tell us what you think!