By IAN YEE

alltherage@thestar.com.my

YOU know there will always be some big-mouthed, know-it-all out there waiting to poop on a party; and last week, that man was former England international Chris Waddle.

Even when Alex Ferguson retired, I had the feeling it was coming. Some genius pundit was going to nit-pick on his success and write a newspaper column saying he was just lucky or something. Thankfully, no one did.

But when Beckham retired, Waddle stretched out those aging muscles and took what must have been a long-awaited swing at the former Manchester United player, saying he was “good but not great”.

“You can go down a list of footballers since the Premier League began and I don’t think David Beckham would be in the first 1,000,” said Waddle. “He made the most of what he had. He has got a terrific image and used it very well.

Let’s be real for a second. Just because Beckham “made the most” of his skill set doesn’t dilute the fact that he was a genuinely great player.

That seems to be the common perception about Beckham – he wasn’t naturally gifted, but he worked hard and became a good (and marketable) player. But does that mean Lionel Messi isn’t a great player because he works hard to make the most of his dribbling skills?

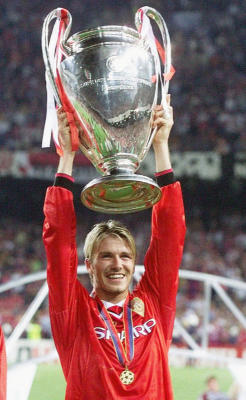

Beckham is a gifted player; there are no two ways about it. He was gifted with an exceptional ability to strike a football, a brilliant footballing brain and incredible stamina. It was a potent combination that made him a runner-up TWICE for the FIFA World Player of the Year award, which is voted for by football managers and captains, not fans.

People only focus on the wonder goals, the brilliant free-kicks and the 50-yard passes, but Beckham’s decision-making and determination were equally important assets.

He always kept the ball well, playing smart give-and-gos whenever possible. And in the final third, he had an uncanny ability to always pick out the most dangerous pass available. Strikers with an instinct to score are celebrated, but Beckham’s unique instinct often goes unnoticed – even by the likes of Waddle.

And then there’s his incredible fitness and determination. When I interviewed Bryan Robson a few years back, he said Beckham is the example he always gives young players because he would train for hours on his own, improving his natural technique.

He consistently ran the longest distances at Manchester United during his peak. When Gareth Bale destroyed Maicon in the Champions League a few years back, people were shocked that he had run over 12km in the game, higher than the average 11km.

Beckham’s Premier League average was 14km. During that famous World Cup qualifier against Greece, he ran over 16km.

Much has been made about his lifestyle off the pitch. But here’s an anecdote for you – when everyone was busy laughing at Beckham for wearing a sarong on a date with Victoria Adams, one tiny detail went unnoticed. A reporter had asked the restaurant for the dinner receipt, and guess what Beckham had? Plain grilled fish, salad, orange juice and water. Yes, he’s a fashion icon and a celebrity. But he was always a footballer first, a very professional one at that.

The application of ability is what makes a good player great. Beckham had some unique abilities, and very few can claim to have applied themselves better.

Crowded at the top

For casual observers of football, and even some die-hard fans, the upper echelons of a club’s hierarchy can be confusing these days.

It used to be simple – the manager was the guy in charge. Now, you have chairmen, chief executives and directors of football all becoming more prominent.

In theory, it all makes sense. The chairperson takes care of matters at the board level, leaving the chief executive to oversee the day-to-day business of the club.

The director of football (also sometimes referred to as sporting directors, technical directors or general managers) provides a link between the suit-and-tie management and the track-suited folk – the manager and coaching staff, many of whom are perceived to be naive by the upper management, and therefore need someone with a bit more savvy to keep them in check.

Within the coaching staff itself, you usually have the manager, assistant manager and first-team coach at the top.

At Manchester United, for instance, Alex Ferguson did not handle training – his first team coach René Meulensteen devised the schedules. Ferguson’s duty was to manage the bigger picture – coaches, scouts, the academy, and, or course, the players.

So at the end of the day, everyone has a key role to play. It’s a well-oiled machine, as major money-spinning organisations should be.

In practice, however, the lines are so blurred that things often get screwed up.

At Chelsea, you have Roman Abramovich, an owner who thinks he’s the manager, sacking and appointing whoever he wants until he gets the players and style of football that suits him.

At Liverpool, we had director of football Damien Comolli throwing away a fortune with only Luis Suarez to show for it. And who got the blame for it? The manager, Kenny Dalglish. When asked to justify the £110mil (RM502mil) he spent on players, Comolli’s excuse was some cool, pretentious reasoning over the big financial picture. A total cop-out.

Roberto Mancini’s great work at Manchester City has also been disrupted by the appointment of chief executive Ferran Soriano and director of football Txiki Bergiristain.

The former Barcelona duo’s influence on the club represents a new shift of power away from football managers to these directors. Managers no longer reign over clubs the way the likes of Ferguson and Bill Shankly did. They now simply answer to their directors of football, who not only determine player transfers, but manager appointments as well.

That didn’t go well with Mancini, who started complaining publicly about club’s failings in the transfer market, obviously angry at being undermined by Soriano and Bergiristain. No surprise then, that the two have recommended a new “holistic” approach at the club that does not include Mancini.

The big question now is whether Manchester United can maintain their “old fashioned” director-less model without Ferguson at the helm.

Ferguson had a great relationship with his chief executive, David Gill, and was allowed to manage the club much like how a director of football would whilst staying involved in the football management side of things.

But Ferguson is a rarity, a football man with enough experience to handle matters on and off the pitch. If you were the chairperson of a football club, would you trust someone like say Harry Redknapp to do the same? Probably not.

More worrying for United fans is the retirement of the influential Gill at the end of the season, with executive vice-chairman Ed Woodward replacing him. Will the club – now a public listed company – continue to place that much responsibility over its fortunes in the hands of a football manager, especially one as untested in the big time as David Moyes? Only time will tell.

Leave a reply