WHEN Nick* was diagnosed with HIV, he was devastated. But, he thought, at least he still had his job in an advertising agency – a job that would allow him to carry on with his life.

But he made the fatal mistake of confiding in a colleague, the very day of his diagnosis. Within a couple of hours, he was summoned into his boss’s office.

“I was asked to leave,” he said with a grimace. “In 24 hours I had lost everything.”

Nick’s story is not unique. Thousands of PLHIV (people living with HIV) face discrimination every single day.

On top of being stereotyped as homosexuals or sex workers, many of them have been fired, or dropped from university scholarships and barred from enrolling as students.

Some even face discrimination from the very people supposed to be treating them.

Sadly, most can’t even get insured.

“It’s like they think we’re going to die tomorrow!” Nick said bitterly. “You would think insurance companies would know PLHIV have the same lifespans as [HIV] negative people.”

It’s shocking that discrimination is still so widespread. A quick Google search soon tells anybody interested to know that there are plenty of drugs available to help lower the viral load of PLHIV to a point where it’s similar to a HIV-negative person.

That means that a PLHIV who regularly takes his or her medication cannot, in fact, spread the virus through bodily fluids, and is pretty much as healthy – and non-infectious – as the next person.

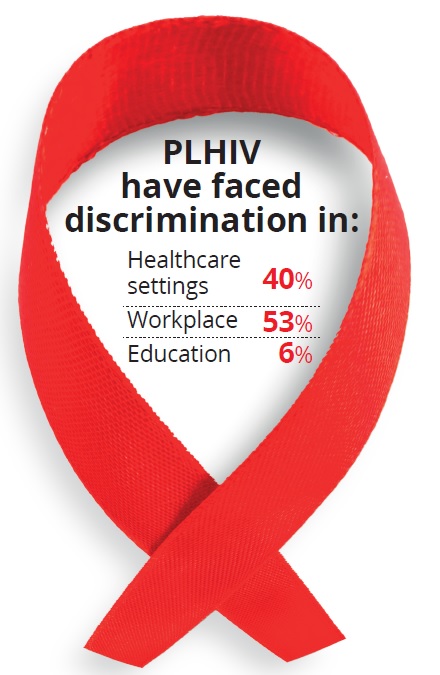

But despite information being so readily available on the Internet, discrimination is so widespread that the Malaysian AIDS Council (MAC) compiled a HIV and Human Rights Mitigation Report in 2015 based on complaints lodged with them by PLHIV.

The report showed that over half of the complaints lodged with them concerned PLHIV being fired due to their status. Forty percent faced discrimination in healthcare settings, and 6% lost scholarship offers.

“Discrimination like this hinders PLHIV from living normal lives,” said Nick. “It’s a medical condition that can be kept under control. It doesn’t affect our ability to work, study, and fulfil our potential.”

The official stats only recorded 15 complaints in 2015, but the real numbers are much, much higher, said MAC president Bakhtiar Talhah.

“We’ve barely scratched the surface when it comes to complaints,” he said. “Too few of them have spoken up.”

Based on MAC’s work on the ground, discrimination is rampant, he said.

“There have been many cases of people losing their jobs, even if their jobs don’t put anybody at risk of contracting HIV, and one very recent case of a PLHIV losing a scholarship.”

Not only do PLHIV face stigma at work, school and even at home – there have been reports of PLHIV having to use a special set of cutlery and even having their laundry washed in separate machines – they also have to contend with snide remarks when trying to receive healthcare.

“Some professionals put their personal beliefs over their job,” said Zaini*, who was diagnosed positive in 2010.

“They seem to think ‘You’re obviously gay or a sex worker, so I’m going to tell you that you’re going to hell first, before treating you.’

“It drives people away from getting tested, when getting tested as early as possible is what needs to be done to arrest the disease early.”

Discrimi-nation

HIV is hardly a new disease – the HIV epidemic first hit Malaysia decades ago.

Ironically, instead of its victims becoming more accepted over the years, HIV’s long-standing presence might actually be a contributing factor to the stigma faced by PLHIV, said Bakhtiar.

“Most of us remember the posters in the 80s and 90s, you know, the ‘AIDS membunuh’ (AIDS kills) ones,” he said. “That message is stuck in our minds.”

But that message, meant to prevent new HIV transmissions, has instead led to discrimination from those who don’t have enough awareness about the disease.

The simple truth is that a lack of education about HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in general is what’s fuelling discrimination, he said.

“A lot of misconceptions surround the disease,” he said. “If everyone thinks ‘There’s someone with HIV in my class, that means I might get infected too,’ then of course PLHIV will be discriminated against.”

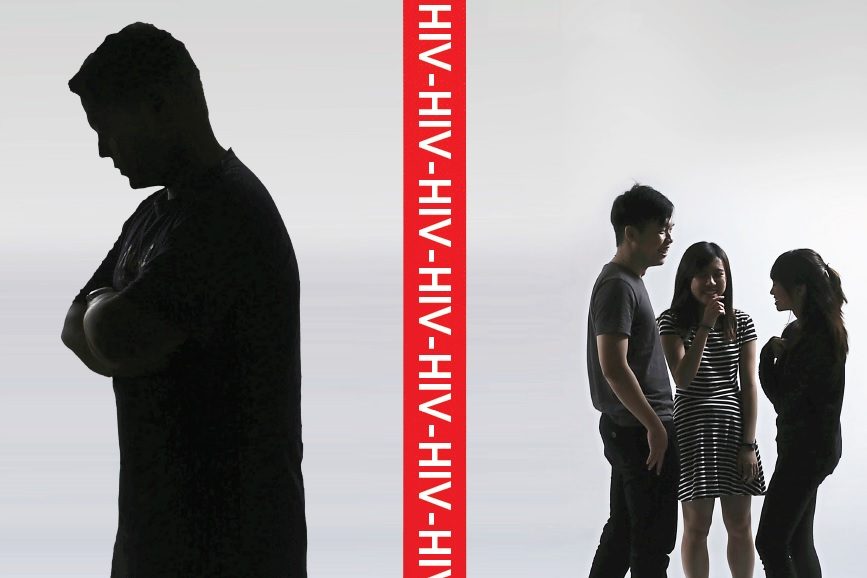

Young Malaysian PLHIV face discrimination not just from friends and family, but also in the workplace, schools, and even in healthcare settings. — Photos: HAFRIZ IQBAL/R.AGE

The key to quashing discrimination could lie in educating people with facts, but a 2016 survey by Durex showed that young Malaysians don’t know the facts at all.

Of the over 1,000 youths aged 18 to 29 surveyed, one in 10 thought HIV could be cured, over 100 respondents would rather not sit next to a PLHIV, and most frighteningly, one-tenth of respondents said they would rather not be tested for STIs due to the “shame”.

“It’s clear that young Malaysians aren’t very well-informed about HIV and STIs in general,” said Rakesh Singh, marketing manager of Durex manufacturer Reckitt Benckiser Malaysia and Singapore.

“It’s important that people know it’s possible to have a healthy lifestyle even with HIV. Without information, it’ll be difficult to contain the stigma.”

What you can do

It’s time that we as a society step up to ensure nobody is marginalised, least of all PLHIV who are fit and healthy enough to take their places in schools and offices. And while it all starts with awareness, we need to do more.

Discrimination is more than just an unpleasant feeling – it leads to serious ramifications for PLHIV. Some even refuse to seek treatment due to snide remarks from medical professionals, which would be detrimental to their health.

“Awareness without action isn’t empowerment. It doesn’t lead to change,” said Mary Pang, executive director of the Federation of Reproductive Health Associations, Malaysia (FRHAM).

“Ideally, the Government should tell people that HIV is not a death sentence, and neither is it a death sentence to sit next to a PLHIV.”

Policy aside, change begins at home, said Rakesh.

“Parents need to understand they’re responsible for their children’s health, and that includes their sexual health.

“We can start the ball rolling with our findings, but there needs to be continuous discussion at home so children are well-informed.”

RELATED: CROSSING A DESERT TO PROMOTE HIV AWARENESS

The Health Ministry has been partnering with NGOs like MAC to organise talks in schools, but there needs to be more work done on the ground. With the rising numbers of young PLHIV – some are diagnosed as young as 15 – there’s a growing need for young volunteers to teach their peers about sexual and reproductive health.

“We lack serious involvement from the youth. Getting the message across to a 20-year-old is far less effective from a pakcik like me,” said Bakhtiar with a laugh.

Jokes aside, the situation is real. With enough information and young volunteers to reach out to those who need help, we may never have to write about discrimination again. And that’s a good thing.

“Currently, some PLHIV are forced to lie in order to get employed and insured,” said Naza. “It shouldn’t be necessary. And when society becomes more accepting, it wouldn’t be.”

*Not their real names

Tell us what you think!