By ELROI YEE

alltherage@thestar.com.my

SHABAZ’S humour is quick. When we ask him what his hopes are for the future, he doesn’t miss a beat to answer in fluent English: “Well I hope to be the president of the United States…” drawing laughter from all present. Seeing the effect of his wit, he smiles, but it quickly fades as he arrives at his point. “We have hopes, of course, but for now, we are here.”

“Here” is a small flat with two bedrooms, which he shares with two other Pakistani families. Two families occupy the bedrooms, one family occupies the living room. Altogether, there are six adults and eight children sharing the unit, the children aged between four and 13.

But “here” is not home. The problem is, they cannot quite pinpoint where home is anymore. The three families, all whom are Christians, left Pakistan to escape from religious discrimination. They arrived in Malaysia hoping for a better life, only to realise that the country, which has refused to sign the United Nations convention on refugees, does not readily recognise asylum seekers’ rights. At the UNHCR office, where they applied for refugee status, they were asked to return for an interview two years later. They show us a card that UNHCR issued to them, which states that their asylum application is being processed.

This photo was taken when we first met Shabaz, a week before our surprise visit. Here, he is planning some Christmas activities for the children. ― Photos: ELROI YEE/The Star

In the meantime, it is illegal for them to work. Many Pakistani asylum seekers are professionals or skilled workers, but they cannot put their education and skills to use. Shabaz, for example, studied in Europe and ran several successful businesses. Instead, they have to take informal employment as waiters, kitchen help, security guards ― anything to put food on the table. It would be a passable life, except that employers often cheat them of their pay. One Pakistani said he was cheated of five months’ salary, and without proper documentation, he and others like him, have no recourse.

Today, Shabaz volunteers at a community-based school run by fellow Pakistani asylum seekers. They teach children from the Pakistani community basic subjects like science and maths, as well as religious studies. The school is run solely by volunteers. It gives their children an education they would otherwise be unable to obtain as asylum seekers in Malaysia.

Our conversation with Shabaz turns to Christmas memories. He remembers better times, when he was a young boy, celebrating Christmas with his family, at home. They would receive carollers at their door on Christmas eve, in the dead of winter, and offer them warm food. Later on when Shabaz became a successful businessman, he celebrated with an eight-foot Christmas tree and distributed food among the less fortunate in his neighbourhood. We ask if he has hopes for Christmas this year. “Of course, we want to celebrate Christmas in a good way, with a nice tree and with presents for the children, instead of having to explain to them why we cannot get them gifts.”

The Christmas tree and presents that we placed at Shabaz’s house while he and the other families were away.

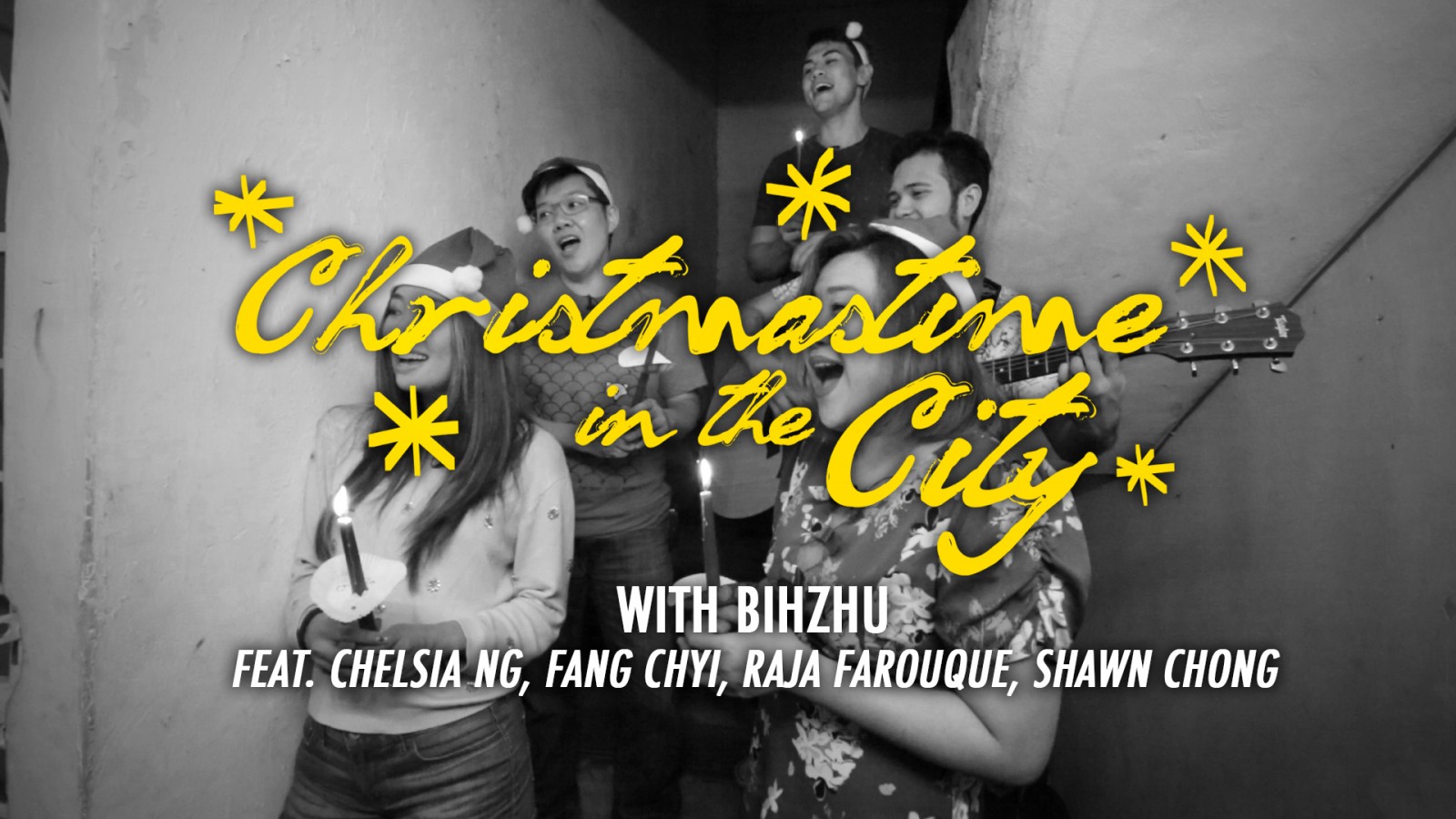

Since we were unable to make him president of the most powerful country in the world, we set about making his more achievable wish come true. While the families were away, we set up a Christmas tree – complete with lights and baubles – and placed presents under the tree for each child. For the adults, we gave them something practical – food items. And for a dash of holiday cheer, we invited local singer Bihzhu to surprise them with a few carols. At the end of our visit, we passed Shabaz a bag of small gifts which he distributed to his neighbours. “I want to thank you for remembering people like us,” he says. “We were just thinking about having a tree, and now we have one.”

Singers Chelsia Ng (left) and Bihzhu (right) giving a surprise performance to the Christian Pakistani family seeking asylum in Malaysia.

But home is still a long way away for Shabaz. A few months earlier, two years since he first arrived, Shabaz finally attended an interview to hear his application for asylum. But UNHCR merely extended his case. He was given a new interview date for next year.

Tell us what you think!