FOR young cheerleaders around the world looking to reach greater heights in the sport – like literally, with bigger stunts and all – All-Star cheerleading is what you should aspire to.

There are six levels in competitive cheerleading internationally.

As athletes move up each level, they are allowed to perform more advanced stunts and formations.

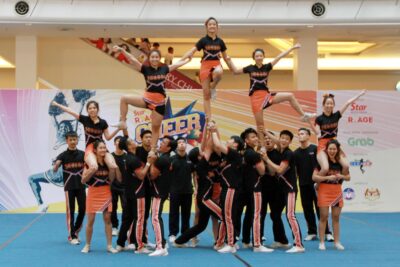

All-Star teams perform only at the two highest levels – five and six. It’s like the Premier League of cheerleading, if you will.

And over the past few years, All-Star teams in Malaysia have been making huge strides, taking part – and winning – in tournaments all over the world.

In fact, their competition winnings and income from performances and coaching jobs bring in enough money for some of them to be full-time All-Star cheerleaders.

“All-Star cheerleaders are generally older (though most teams have a few teen prodigies on their books) and know their bodies better, which is why they’re allowed to perform more difficult stunts like higher pyramids, and inversion and twisting skills,” said cheerleader Leng Kim Swee, 28, coach of the Rebels All-Stars, a local team established in 2006.

The local cheerleading community has sure come a long way since 2000, when Malaysian cheerleading had its first large-scale competition – CHEER, an inter-school tournament, organised at the time by The Star.

Back then, the stunts and routines were relatively simple.

Now, with just weeks to go to the 15th edition of CHEER, Malaysian cheerleading has become so advanced, many of the students participating in CHEER 2014 will go on to have semi-professional cheerleading careers.

Careers in cheer

So what exactly is a semi-pro cheerleading career in Malaysia like?

“There are roles for those interested in part-time and full-time careers,” said Lim Chee Wei, head coach of the Awesomes All-Star team and co-founder of Cheer Aspirations, a company that specialises in cheerleading equipment and training.

“Coaching is a very flexible career option. You can juggle it with other commitments (like studies or day jobs).”

And it doesn’t just need to be cheerleading coaching.

The Cheer Aces All-Star team, co-founded in 2010 by former CHEER participant Loh Kheen Ho, 25, now runs an academy as well, providing cheerleading and gymnastics training.

The team has 60 members now.

How Loh first got into cheerleading is a funny story.

“I joined because I liked one of the cheerleaders in my school team (the Vulcanz from SMK Seafield)!” he said.

“But I ended up falling in love with the sport, and I’ve stayed with it for almost ten years! Cheerleading isn’t just a hobby for me now. It’s my life.”

Those who are a little more entrepreneurial can now sell cheerleading equipment, uniforms and even music (specially mixed tracks for cheerleading routines) to fulfil the demand from this growing industry.

Then, of course, there’s performing.

Top All-Star teams are paid to perform at events and functions about 10-20 times a year.

The cheerleaders can take home up to RM250 each for performing a single routine, according to Lim.

“In the past, I wouldn’t be able to say that cheerleading is a promising career,” added Lim.

“But now, we have quite a few different options.”

Tough game

Just like it is with cheerleading, being in the All-Star game has its share of ups and downs.

For starters, training for competitions can be brutal, especially when most of the cheerleaders have to worry about their studies or day jobs.

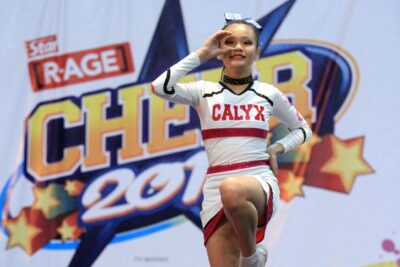

Rebels flyer Adele Ng, 22, gets questions like: “Why are you working so hard when cheerleading isn’t even a real sport?”

And then there are the injuries, especially for flyers like Ng, who regularly gets tossed over 10 feet up in the air. “My friends are so used to seeing me covered in bruises, they don’t even bother asking anymore.”

But despite all that, Ng said there’s nothing quite like the feeling you get when you nail a cheer routine.

“When I’m up in the air, I feel confident! I don’t know how to describe the feeling, but I’m smiling the whole time. If I were to miss one or two cheer practices, I’d get ‘cheer withdrawal syndrome’,” she added with a laugh.

The business side of things ain’t easy either. The Malaysian cheerleading season only lasts for a few months a year, so during the off-season, Loh said businesses like his tend to struggle.

“We just have to be smart, and be creative to find different sources of income,” he said.

For the male cheerleaders, there are obviously other considerations too – like whether the people around you will accept you being a cheerleader at all.

Things are better these days, but when all-boy teams were first introduced at CHEER a few years ago, the guys would get some pretty serious abuse.

“We got called ‘soft’ and ‘pom pom boys’,” said Lim.

“But it made me tougher mentally; and when we nail those stunts and gymnastic skills, that’s when I feel the most masculine!”

Cheerleading in colleges

The problem with All-Star teams in Malaysia, however, is that it has stunted the development of college and university cheerleading.

Tan Yee Ming, an experienced cheerleading coach, internationally-certified judge and co-founder of Cheer Aspirations, explained: “It’s hard for cheerleaders to be motivated to start or build up their own college teams when they can jump straight from school to All-Star cheerleading.”

On the other hand, All-Star teams increase the level of the sport, said Tan.

And, to be fair, Tan said there have been All-Star members who’ve started college teams.

“People need to realise that they can compete at college-level,” said Beverly Hon, president of the Cheerleading Association and Register of Malaysia (CHARM).

“It’s important to build up the sport from the grassroots (outside of All-Star teams) because there needs to be a big enough pool of talent for the sport to grow.”

Leave a reply