Virtual bullying

One in three Malaysian children are victims.

By KEVIN TAN and PHYLLIS HO

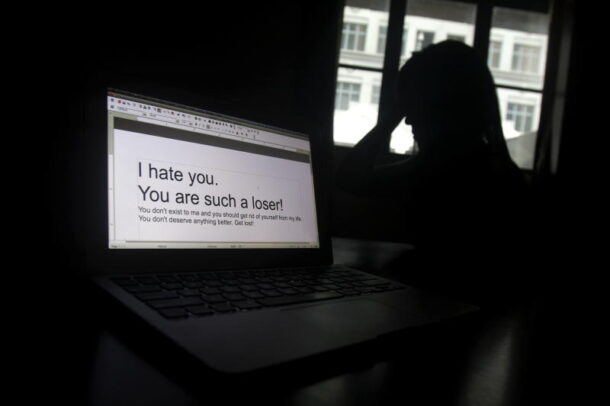

FOR Tam Xueh Wei, 16, being verbally abused on the Internet is nothing new – just because she’s a Justin Bieber fan. She’s been called names so bad we’re not even allowed to *bleep* them out in print.

Like so many teenagers around the world, Tam has a pop idol she looks up to and is part of a “fandom” (a social network-based fan community).

But abuse towards teenagers in fandoms, and social networks in general, is so common now that Tam just brushes it off, saying she’s “used to it”; though she did eventually give up her Bieber fan account on Twitter because “drama is not her cup of tea.”

Not every teenager would be able to deal with abuse as well as Tam, though – especially if they’re half her age.

According to a recent Microsoft survey, 33% of children aged 8-17 in Malaysia have experienced some form of online bullying; and only 4% of them said their school had a formal policy to address the issue.

And it’s not just young, teenage fan girls who’re getting abused. Local YouTubers have spoken up regularly about Internet “trolls”, a term to describe people who persistently post negative comments online to provoke someone.

It has become a wider part of Internet culture, and everyone from footballers and reality TV stars to the average Malaysian teenager is a potential target, largely thanks to the anonymity afforded by the Internet.

Take for instance the case of American news anchor Jennifer Livingston, whose story has spread like wildfire over the Internet. Livingston was the target of an online “bully” who emailed her saying she was obese and not a “suitable example for this community’s young people, girls in particular”.

Livingston’s video in response to the bully, in which she urges other victims to stand up to their trolls, immediately went viral.

But Livingston’s case is an exception. Very few have the platform she does to respond to tormentors. And with another recent survey revealing that teenagers in the Klang Valley spend an average of SEVEN hours a day on the Internet, more needs to be done about cyberbullying.

Mind games

According to the president of Malaysian Psychiatric Association (MPA) Dr Abdul Kadir Abdul Bakar, cyberbullying can have serious psychological consequences on both the victim and the bully.

“Victims could suffer from depression, anxiety and sometimes even psychotic illnesses. Bullies will develop antisocial personalities and they could also be suffering from depression,” said Abdul Kadir.

Britney Chua, 22, for instance, has been a victim of cyber stalking for over three years. She endured hundreds of abusive messages on social media and email before finally alerting the authorities.

“I was very scared, paranoid and felt like shutting myself out from the world and everyone else,” she said. “I could not sleep well for months and I would cry out of fear every day.”

Noticing this alarming trend, the Women’s Centre of Change (WCC) started a campaign to create awareness of cyberbullying, and what victims can do in the event they are abuse online.

WCC programme director Dr. Prema Devaraj said the Internet gives much more power to bullies as they can now easily make hate content available to the public.

“With information and communication technologies, the perpetrator can ensure that lots of people have access to the acts of cyberbullying.

“The bully can also extend his or her power beyond a particular location. Bullying is no longer just taking place in the victim’s classroom. It could be happening to the victim while he or she is at home, at work or even on holiday,” she said.

No laughing matter

According to CyberSecurity Malaysia acting chief executive officer Zahri Yunos, cyberbullying can take on many forms, such as harassment, impersonation, flaming and cyberstalking.

CyberSecurity Malaysia is the national cyber security specialist agency under the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI), and cyberbullying victims can seek help through their Cyber999 service (cyber999@cybersecurity.my).

“The worst case of cyberbullying we’ve received was from a male complainant who was bullied and threatened by a woman he met on Facebook.

“They started chatting as friends, and then started an online relationship. When the relationship evolved, the woman asked him to open a Skype account so they can have video chats.

“One day, the woman lured him to take his clothes off in front of the webcam, and suddenly the chat was disconnected. After a while, the woman sent him a link to the video. She threatened to circulate the video to all his Facebook friends unless he paid her RM2,000,” said Zahri.

Another group joining Microsoft and WCC in campaigning against cyberbullying is DiGi, who launched its DiGi CyberSAFE programme late last year.

The programme has already gone to 220 schools across the country to provide education on safe Internet usage, and one of the aspects it focuses on is cyberbullying.

“The most common type of cyberbullying taking place in Malaysia is harassment, where people post up embarrassing pictures of others or spread rumours around,” said Philip Ling, senior corporate responsibility practitioner for DiGi.

Although most of the harassment done by young people are intended to be jokes and pranks, Ling wants them to know that these actions are not okay and can be hurtful to others.

“The best way to prevent cyberbullying is for parents to teach social etiquette to their children, especially online.”

According to DiGi’s research, they have found that teens in the Klang Valley spend more than seven hours a day online, compared to the average of two to three hours in other states.

“Most parents are aware that their children are on the Internet, but they do not actually know what they are doing,” said Ling.

According to DiGi’s booklet on online safety, the top five things teenagers do online are online gaming, social networking, instant messaging, video and music streaming, and web searches.

Cybercrime

Technically, there is no provision under any penal law which specifically describes “cyberbullying” as a criminal offence.

However, cyberbullying can be a crime if it fulfils Section 503 of the penal code and/or Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998, which considers any obscene, indecent, false, menacing or offensive comment or communication with the intention to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass as an offence.

This includes threats that can be damaging to a person, their reputation, and their property.

DSP Mohd Lazim Ismail, from the Royal Malaysian Police’s Commercial Crime Investigation Department, says that to define whether an act of cyberbullying is a crime depends wholly on the victim.

“We base our decision on the person who is on the receiving end. If the act is meant as a joke among friends, and the ‘victim’ interprets it the same way, then it is not an offence – even though it is a stated offence according to the law,” Lazim explained.

Those guilty of an offence will be liable to a fine up to RM50,000, imprisonment up to one year, or both.

“We have investigated many reported cases, and we find that many ‘cyberbullies’ do not know they have committed a criminal offence, because they only did it for a laugh,” Lazim said.

“However, if the victim finds that he or she is being offended by someone on the Internet, they should report it to us so we can investigate.”

Lazim’s advice is to be careful when criticising someone online, as what may seem like perfectly constructive criticism to you, might seem offensive to the person on the receiving end of it.

“People need to be aware of the law in regards to cybercrime, because they can be charged as long as someone finds it offensive and reports it,” he added.

Don’t be silent

The most important thing for Abdul Kadir is that victims of cyberbullying realise they should not accept any form of bullying.

“Don’t accept that you’re being bullied. Immediately inform your parents, or the authorities at your school or workplace. The important thing is not to tolerate bullies.

“If you’re a victim, then you need psychological help because being constantly harassed by someone online is a type of trauma and by getting help, you can learn how to overcome it.”

DSP Lazim says cyberbullying victims can contact the police, or services such as CyberSecurity’s Cyber999 (see sidebar).

Cyber stalking had led Chua to live in fear and depression, which she took two years to recover from.

Looking back, she now realises she should have dealt with the problem head-on, instead of running away from it.

“Dealing with it didn’t mean having to deal with my stalker,” she said. “I just had to face the problem and tell someone I could trust. I eventually did, and I wish I had done it earlier.”

And to those who are still struggling to find the courage to stand up to online bullies, Livingston, in her video response to her bully, said: “To all of the children out there who feel lost, who are struggling with your weight, with the colour of your skin, your sexual preference, your disability, even the acne on your face, listen to me right now.

“Do not let your self-worth be defined by bullies. Learn from my experience, that the cruel words of one are nothing compared to the shouts of many.”

Leave a reply