The river named Ong Laba used to be a fishing spot, says Said. He knows because he used to fish there, at a point where the river runs near his village of Kampung Ong Jangking, an Orang Asli settlement in the forests of northern Peninsular Malaysia. There used to be flowing streams feeding into wide pools of water, amid large boulders mottled with sunlight filtered through trees.

A perfect spot to find lunch, or maybe take a bath.

Today the river is shallow, its banks thick with the reddish sediment that is the trademark of logging activity. A sign that, somewhere upstream, the red-hued clay soil beneath the forest topsoil has been churned up. On one side of the river bank, where the land slopes up through secondary forest to where a logging road runs, the same red earth lines the seams of the roots and rocks.

"When it rains, the mud from the logging road up there washes down into the river," Said points out.

"Look, you can see it."

He digs a finger into the sediment. It is reddish, smooth, and mud-like, unlike the greyish gravel and sand common in the other rivers. "It’s all finished," he says.

He whips out a mobile phone and takes a few photos, documenting the damage. In a landscape far removed from urban centres, the experiences of Orang Asli communities like Kampung Ong Jangking have little hope of wider attention.

But village journalists like Said are making sure their stories will be told.

Suddenly, Said goes quiet. Beyond the trees, the sound of machinery interrupts the forest. It grows louder and louder, ominous and approaching. Said listens, almost in awe.

"That’s them, another santaiwong is passing through."

For the indigenous Orang Asli who still live in Peninsular Malaysia’s forests, clean rivers and healthy forests are not merely aesthetically pleasing, but serve life’s basic necessities – food, water, building material, sanitation, even spirituality. Many of their rituals involve specific plants they source from their environment.

A broken forest or river, means a part of their lives is broken.

So in 2019, when logging resumed in the area around Kampung Ong Jangking, the Orang Asli already knew what was at stake. This is not the land’s first brush with logging.

The Orang Asli can point out the old logging roads, and remember. These red-ochre mud tracks trample everything in their path.

In one spot, Said points out where a stream used to be. But the logging road needed to pass, so a crude bridge was made by dumping logs and earth into the stream, until the stream was no more.

The Orang Asli had to dig a trench around the disused bridge, so that water would not remain stagnant.

Today, that mound of logs and earth is still there, years since the road was last used to carry the santaiwongs – those loud, lumbering lorries that look like something out of a dystopian movie. They heave and hiss exhaust smoke as they grind up the logging roads into the forest, returning with stacks of logs as thick as the santaiwong’s wheels, balanced on their carriage.

In their wake, red earth.

Faced with the irreparable destruction of their environment, the Orang Asli decided to make a stand, and they made it at a point where the logging road runs close to the Ong Laba river, almost within sight. There, they built a blockade of sticks and branches that seemed childish in comparison to the steel and diesel of the santaiwongs.

The blockade wouldn’t stop the machines, so the Orang Asli themselves, women and children included, stood in the way.

They faced down the machines dressed in their traditional best – headdresses woven of leaves, bracelets and necklaces made of seeds, red and white paint on their faces.

These symbols of Orang Asli identity, now worn as symbols of resistance.

The surrounding villages came to add their bodies to the human blockade, many of them already protesting encroachment in their own villages.

The key contention in this dispute was whether the land belonged to the Orang Asli. The forests they claimed to be protecting was gazetted as the Air Chepam Forest Reserve in 1992. In Malaysia, forest reserves can be earmarked as production forests for timber. But the Orang Asli have always lived in and foraged these same forests, and claim it is part of their ancestral lands.

The standoff lasted days. After a period of negotiation, where state officers crossed over the blockade and tried to talk down the Orang Asli, the battle lines became clear. On one side, the Orang Asli wanted the forest protected. On the other, loggers and state agency officers wanted the law enforced.

Even JAKOA, the Department for Orang Asli Development, the state agency charged with advancing the Orang Asli in Malaysia, stood on the side of the loggers.

Machines couldn’t force this blockade open, but men could. Officers from the state forestry department and police dispersed the protesters and detained six Orang Asli over two separate occasions.

Handcuffs were applied on the protesters, chainsaws were applied on the blockade.

No journalists were there, perhaps the story was too far off the asphalt roads. So the Orang Asli filmed and took photos on their own and sent them to activists, raising some media attention, which led to interventions from a federal minister calling for the arrested Orang Asli to be freed.

After that, the logging stopped. Quite a feat for a tiny village of around 20 families.

But the reprieve was temporary. In June 2020, soon after COVID-19 movement controls were lifted, logging vehicles reappeared.

Before dawn, the people of Kampung Ong Jangking are already awake. In the pitch-dark, torchlight peeks out through the slits in the bamboo walls of the houses.

One man goes to fetch water from the nearby river. Two women start preparing breakfast.

Anjang, one of the community’s leaders, calls out to the houses on the other side of the settlement. "I’m asking them to go watch the blockade," he says. Anjang is the talker of the village, one of the few who finished secondary school, and often takes the lead when communal action is needed.

The women arrive with coffee and tea, and fried meehoon.

Over a hot breakfast, the men chat amiably in the early morning chill, in the raised bamboo hut that is their community hall.

But before they can finish, a santaiwong rumbles in the distance, and the men sprint off in its direction. The village journalists, off to document.

Since the logging vehicles returned in June 2020, this has become their routine. Every morning, they hide near the blockade and take photos and videos of logging company representatives tearing it down.

Then they document the procession of santaiwongs rumbling in and out of the forest, ferrying huge logs. In a notebook, Anjang lists down the time and description of each vehicle, while the others take photos and videos.

Although the blockade is built at the same spot they last made their stand in 2019, they are adopting a different strategy, to legalise their ancestral land claims in court.

Instead of confronting the logging company, they are documenting how it is ignoring the Orang Asli’s objections.

It might seem like a futile exercise, but this evidence could be crucial in court.

In past cases, Malaysian courts have ruled, based on common law principles and the Federal Constitution, that the Orang Asli are entitled native title rights to their ancestral lands, if they can prove the legitimacy of their claims in court.

In this matter, evidence of continuous assertion of control over the land is important. If you believe you own the land, surely you would defend it.

Photographs and videos of the logging company tearing down the blockade is evidence that the company is openly ignoring the Orang Asli’s assertions of control – evidence that could tilt a court case in their favour.

Today, Anjang’s stakeout is behind dense foliage, almost directly above the passing lorries, where the hill was cut off to make the logging road. Said’s stakeout is on the opposite side, on the next hill. There should be no need for subterfuge, but they remember the arrests during the last blockade and the confiscation of their mobile phones and motorcycles by authorities, and prefer to avoid a repeat.

Whenever they hear an approaching santaiwong, they call out to each other. Mobile phones are quickly strapped to makeshift tripods fashioned from branches, and in an instant they disappear behind the foliage.

Said has strapped a leaf in front of his phone for added camouflage. Anjang has his notebook and pen ready.

Between them, on that strip of red earth, the santaiwong roars past – clanking, hissing, grumbling, turning up red earth. Then the forest sounds return, until the next lorry passes.

Then the forest sounds return, until the next lorry passes. In the evening, after the loggers call it a day, the Orang Asli rebuild the blockade.

Some 370km away from Kampung Ong Jangking to the south, in an air-conditioned office, the village journalists’ photos are taking a professor by surprise. In particular, those that show the condition of the logging roads.

"I have been to other logging sites before, but I’ve not seen conditions like these," he said. "This is at a critical level."

Prof Mohd Hasmadi Ismail lectures on forest extraction at Universiti Putra Malaysia, a government university renowned for its forestry programme. On a computer screen before him, are photos of the logging roads snaking past Kampung Ong Jangking’s land, pinned on a digital map.

Even as village journalists documented the blockade, they regularly walked the logging roads and rivers to gather evidence of environmental damage.

Working with them, we compiled a digital map of the environmental destruction wreaked by the logging activity.

Time and again, the photos and videos would show mud spilling from the logging road into rivers. Or landslides crumbling onto the logging roads. Or bridges that throttle rivers into muddy spouts.

The river most damaged is the Ong Laba river, which remains heavy with sediment some three kilometres downstream, where it runs close to Kampung Ong Jangking.

At the point where Said used to fish.

A little further downstream, at the point where villagers usually ford the river on foot when they head to town, photos show the river overflowing its banks during rains, likely a consequence of the logging upstream.

|

A digital map of the impact of logging in Kampung Ong Jangking |

|

"Sediment from upstream will be deposited downstream, and make the river shallower," said Prof Hasmadi, as he examined the photos. "So during heavy rains, the river’s water level will rise faster."

Although the logging site in question is around three kilometres away, the logging road runs within a kilometre of Kampung Ong Jangking, while the logs are gathered at a log yard just 300 metres from Kampung Sungai Papan, another Orang Asli settlement.

Research has shown that logging roads and log yards are as harmful to the environment as logged forest, if not worse. The weight of the santaiwongs and other machinery compacts the soil and leaves it barren, even years after logging has ceased. Reforestation of logging roads also takes longer than the logged forest itself.

Other scientifically proven effects of logging roads include increased incidences of landslides and sediment accumulation in streams, leading to poor water quality.

"Seventy percent of environmental damage from logging activities comes from the logging roads – the construction of the roads as well as its use by heavy machinery," says Prof Hasmadi.

"The impact is worse when logging roads cross rivers, or are built too close to rivers, violating guidelines," he says, noting that many logging companies don’t pay enough attention to building proper bridges.

"Logging roads usually don’t impact human communities, but when they affect rivers upstream, the sediment will flow downstream and that’s when communities are affected," adds Prof Hasmadi.

Photos and videos taken by the Orang Asli of Ong Jangking show how logging activity affects their environment. Runoff from the logging roads and bridges leave rivers heavy with sediment, even many kilometres downstream.

Seen on a map, these logging roads appear as little more than tiny scars on the face of the earth, but each new scar brings a change in the environment that only the Orang Asli need to bear.

This is why almost all timber certification standards around the world require logging companies to ensure their work does not impinge on the rights of indigenous communities.

Timber or wood certification helps buyers identify timber products that originate from sustainably- managed forests. Buyers are more likely to purchase certified products to avoid the bad publicity if found procuring from unethical supply chains.

While timber certification is largely seen as a positive step towards sustainable forest management, there have been critics who doubt its effectiveness.

Malaysia has developed its own timber certification standards, under the Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC). In Peninsular Malaysia, forests in each state are considered a single Forest Management Unit (FMU). MTCC awards the certification to the state forestry departments, who oversee the FMU of their respective states.

The Perak FMU, where Kampung Ong Jangking is located, is MTCC-certified, and therefore needs to meet certification standards.

Among other indicators, this includes ensuring that logging does not "threaten or diminish the resources and tenure rights of indigenous peoples". Logging companies are also required to seek the free, prior and informed consent of local communities that will be affected by the logging activity, and put in place mechanisms to address their grievances.

According to the Orang Asli, they have been actively objecting to the logging since 2018. They produced a letter dated Nov 13, 2018 addressed to MTCC, protesting the "intrusion of logging onto (Orang Asli) ancestral land".

In July 2019, they blockaded the logging road in protest.

Despite these clear objections, Perak’s MTCC certification for forest management was renewed on Jul 11, 2019, following an audit conducted from Feb 18 to Feb 23.

Under MTCC’s standards, certification is renewed subject to independent audits conducted every five years. Between these recertification audits, surveillance audits are conducted every year. Auditors are also obliged to investigate non-compliance when reported. Currently, the only company actively conducting MTCC audits is SIRIM QAS International – a subsidiary of SIRIM Berhad, the national standards and quality control body under the purview of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

It is understood that residents of Kampung Ong Jangking have sent the evidence they compiled to MTCC, SIRIM QAS International, the forestry department of Peninsular Malaysia, and the Perak state forestry department in a letter dated Dec 7.

MTCC, in an email response, confirmed receipt of the Orang Asli’s complaints, and said the actions taken by the state forestry department will be assessed by the auditors in the coming surveillance audit in early 2021.

We approached the state forestry department for a response, and presented the same evidence to the director Datuk Mohamed Zin Yusop and deputy director Tuan Haji Ramli Mat on 1 Dec. They asked for a week to investigate the matter.

On 8 Dec, the department responded saying their investigations confirmed at least four instances of non-compliance to regulations on logging roads and bridges, and the logging company will be issued a compound for each instance.

This might seem like a victory for the village journalists of Kampung Ong Jangking, but it is a hollow one.

Each compound is understood to cost RM1,000 – loose change for logging companies. According to a price list on the Malaysian Timber Industry Board’s website, hardwood timber is worth between RM1,020 to RM5,000 per tonne, depending on the tree species and quality.

The three-axle santaiwongs used by the logging company in Kampung Ong Jangking are allowed to carry between 13 to 27 tonnes per load, according to forestry department guidelines.

Profits from a single load of timber would likely be enough to pay for these fines several times over. At the peak of logging activity, village journalists recorded as many as seven fully-loaded santaiwongs a day leaving the forest.

While logging companies leave with the logs, and their profits, the Orang Asli are left to live with the broken landscape, which affects them beyond mere access to natural resources.

"For the Orang Asli, when their forest is destroyed, it’s equivalent to a church or museum being desecrated by outsiders, and they can only watch on helplessly," says Colin Nicholas, the founder of Center for Orang Asli Concerns, who has researched and worked with Orang Asli communities for over 30 years.

"Obviously, the environment is affected, but the more important effect on the Orang Asli is it tells them that, ‘Hey you have no rights to this land, I can do whatever I want, and you can’t do anything’."

Ramli, the young headman of Kampung Ong Jangking, looks out at the land below him. On one side of the hill is his uncle’s farm, freshly cleared and now sprouting crops like tapioca, chilli, curry trees, and tobacco.

On the other side, where Ramli is staring, is the log yard – a large tract of cleared land, flattened by tyre tracks, where piles and piles of logs sit in the evening sun.

This is where the santaiwongs bring their cargo. From here, lorries with twice the capacity of the santaiwongs will carry the logs to sawmills.

There the trees will finally become products.

Ramli is taking photos with his phone, as he has done consistently over the past weeks, documenting the logging at his village’s doorstep.

With friends, Ramli can be quite the joker. But atop this hill, he is silent. From here, he can hear the loud conversation of the workers, brash and confident, floating in from below.

At one point, he suddenly stands up in full view of them and takes more photos.

"They are saying 'If he wants to take photos, lantaklah!'," Ramli says. "So, lantaklah." Screw it, he says.

"We are living like this, and they’re enjoying themselves."

So he stands there, atop that hill in sunset, taking photos, and he says nothing but his face bears this new insult along with the many insults his people have received over the years.

Not just the repeated encroachment on their land. There is the bullying many Orang Asli experience in school. The name-calling, that even today happens when they visit the town. The constant stream of government agencies implying their way of life, and religion, is backward.

In official documents, their animistic belief is simply listed as "No religion". Worse, in the 1980s there were government-instituted policies to Islamise Orang Asli communities.

Ramli himself was unable to marry his wife because she was somehow registered as a Muslim, and he refused to convert. In Malaysia, non-Muslims cannot legally marry Muslims without converting.

So his children are officially fatherless.

On Nov 16, his family welcomed a new addition, and he is still trying to find a way to get a birth certificate that lists him as the father.

All these insults, like soft slaps to the face, again and again, and his face bears them all.

Even his daughter’s death, he seemed to take as an insult.

We received news of Jessica’s death at night, in September 2019. This was a period of time just after they had managed to ward off the loggers following the blockade last year. We had known she was ill, but it seemed she had turned a corner after Ramli brought her to a private clinic in town. They often distrust government hospitals, even though treatment there is free, and would rather pay for treatment elsewhere. The doctors and nurses at private clinics don’t scold them, they say.

Moreover, government agencies are often seen to be siding with logging companies in opposition to the Orang Asli.

But when Jessica’s condition worsened, Ramli brought her to the government hospital in the nearest town. That’s when he called with the news.

He sounded angry over the phone, in the way deep grief is often expressed.

"Let me tell you," he said. "My daughter has died."

She was two years old.

Around the same period of time, a number of children from the village fell sick with the same symptoms: coughing and fever. Nine other children were hospitalised in the following weeks, with one – Said’s six-year-old daughter – narrowly avoiding death after spending over a week in intensive care.

The health department made emergency trips into the village, to try to contain what appeared to be an outbreak of unknown cause. At one point, they insisted on hospitalising seven villagers at the same time for further observation. They even took water samples from the river for analysis.

In the end, there was no conclusive evidence of an outbreak. Samples from the hospitalised children found some with influenza A, some with influenza B, and one with leptospirosis. However, the department’s prompt action likely prevented more deaths as even those with mild symptoms were given treatment.

Sadly, sickness continues to be common in Kampung Ong Jangking.

In September, when logging was in full swing, Ramli’s mother was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and at the time of writing is still living at a transit facility undergoing observation. Another man spent days in intensive care fighting leptospirosis.

Leptospirosis is a bacterial infection often transmitted through the urine of infected wildlife, which contaminate water sources or stagnant puddles.

Like the puddles left behind after logging activity, and along logging roads.

Many scientific studies have linked spikes in infection numbers to deforestation, not just for leptospirosis but for many other zoonotic diseases, carried by wildlife and insects emerging from the disturbed landscape.

A few months prior, health department officers were concerned enough about the threat of mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever that they sent mosquito nets to the village.

In November, Ramli’s brother Johari was hospitalised for almost a week for dengue fever.

"When I go to the forest these days, the mosquitoes are scary, the way they cover your arm," says Ramli. "It wasn’t like this before."

It is almost impossible to prove that any of these inflictions – the broken rivers, the poor health, the mistrust towards state agencies – are a direct result of logging activities, especially in court where logging companies have a clear advantage in terms of access to the state bureaucracy and larger resources.

All the community can do, is to stockpile evidence in their favour, and send it out into the world.

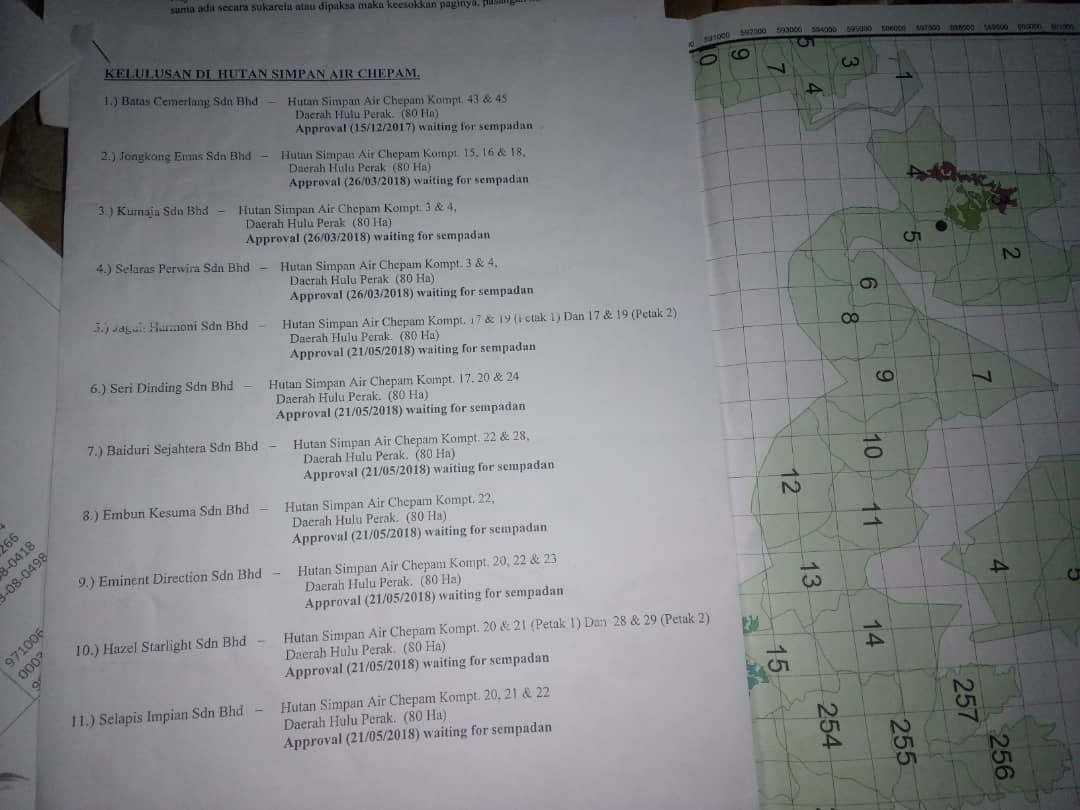

In early September, village journalists uncovered documents that showed large swathes of the Air Chepam forest reserve had already been approved for logging since 2018.

These documents were presented to them when logging company representatives showed up at their village informing them of the impending logging activity. A few photos were surreptitiously taken.

A list of compartments approved for logging in the Air Chepam Forest Reserve, along with the companies involved. One of the approved compartments includes Kampung Ong Jangking.

These logging concessions would be within the ancestral boundaries claimed by at least seven Orang Asli settlements. The area approved for one particular concession appears to include the site of Kampung Ong Jangking’s settlements.

If these logging concessions proceed, there will be little forest left which the Orang Asli of Kampung Ong Jangking can call home. Their quality of life – so dependent on the forest – will continue to degrade.

However, there could be a win-win solution: "If you recognise the Orang Asli as co-owners of the land, the land can be collaboratively managed in a way that benefits both parties," said Colin Nicholas, citing three examples where there has been precedent of such agreements.

The Endau-Rompin National Park in the southern state of Johor initially wanted to evict Orang Asli from its boundaries, but courts ruled the eviction to be unlawful and instead affirmed the Orang Asli’s native title rights to an area that includes portions of the Park. Subsequently, a consent agreement between the parties allowed the Park to remain as a conservation area, with the Orang Asli agreeing not to cultivate new land within Park boundaries.

In Pos Belatim and Pos Balar, two Orang Asli settlements in the northern state of Kelantan, courts have ruled, also in consent agreements, that the Orang Asli would be granted native title over their settlements, while the state agreed to ban logging in large swathes of the surrounding forest, to preserve the Orang Asli’s water catchment areas and hunting grounds.

The compromise in these cases is found in the Orang Asli’s willingness to relinquish native customary title over their wider foraging grounds, and agree to having title only to their settled and cultivated lands. In exchange, the state agreed to protect the wider landscape around them from logging, and allow continued access for traditional practices such as hunting and rituals. In Pos Belatim’s case, courts had initially ruled 9,361ha to be gazetted as native customary land.

Over the past months, an entourage from Kampung Ong Jangking has been taking regular trips down memory lane.

Armed with their mobile phones and cameras, they hike to their destinations: one is an imposing tree strangled with roots. Another is an old fruit tree. Still another, a strange steel structure on a hill. Then there is a brook-side rock with strange markings, and many more.

Unremarkable sites to the uninitiated, but rich with stories. The old fruit tree used to feed their ancestors. The strange steel structure is said to have been built by the British. The brook-side rock is where a young girl had her hand trapped, according to local mythology. There are old grave sites too, which are archaeological evidence of their ancestry on the land, and also where Jessica rests.

These are stories that tie their community to the land, since time immemorial. Which is what they need to prove in court, for the land to be recognised as their ancestral land.

Beyond their history with the land, they also need to prove their community’s dependence on the land, that the land is an ecological niche inseparable from their identity. They need to prove that their community is distinct from the mainstream population, with its own customary methods of managing the land and its populace.

Essentially, they need to prove their civilisation, to a bureaucracy that often denies it.

While volunteer lawyers are advising them on legal matters, the evidence to support their ancestral claims will need to come from the community.

So the village journalists are now amateur historians, not only writing the first draft of their community’s history, but seeking its very roots, entrenched deep in the land.

Unlike mainstream history, theirs is rarely documented. So oral history from their elders becomes their primary source.

Jekeh, Ramli’s uncle, stands before the giant tree and tells its story in their native language. He is as animated in storytelling as he is in person.

Then he explains how they find potable water from the aerial roots of certain trees, as another elder demonstrates. The root is lifted high and clear water trickles from it into his mouth. He lets out a dramatic sigh, to show just how refreshing the water is.

Said, a generation younger, records all this on his phone, then uses a GPS app to mark the locations, digitising these oral histories in a format that urbanites can understand.

Around him, the children of Ong Jangking, another generation younger – wearing headdresses of woven leaves, necklaces and bracelets of seeds – watch on.