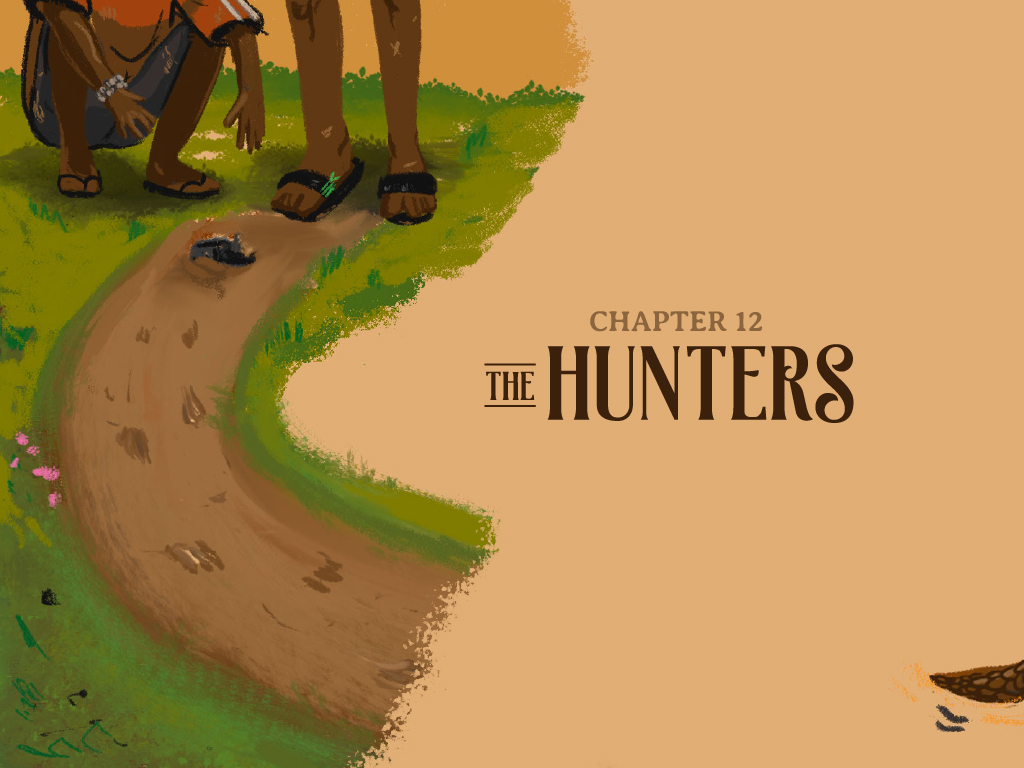

njang and Ramli, two brothers from the indigenous Temiar community, are squatting by a dirt road that runs through a plantation area, pointing at what they claim are pangolin tracks.

“Here, these are its claw marks,” Anjang says carefully, fingers hovering above the soil. “It went this way, you see?”

We could not see. To our eyes, it was just loose soil and some leaves. As Anjang tries to help us discern the tracks, Ramli is already waist deep in undergrowth, following the trail. The tracks were too old, though, and he returned empty handed.

The Temiars are an indigenous people group whose traditional land sits on the northern edges of Peninsular Malaysia’s central forest spine. Even though Anjang and Ramli’s village is in the heart of the jungle, they and their hunting entourage would travel almost an hour by motorcycle to this stretch of dirt road to hunt pangolins.

“All of this used to be jungle,” says Anjang of the hills around us, now stripped of its original rainforest and terraced for cash crop trees like rubber or oil palm. But those cash crops were never planted, and our indigenous guides don’t know why. They do know that it has turned the place into an easy hunting ground for pangolins.

“They cross this road to look for food, then head back there to sleep,” says Anjang pointing at a distant hill still covered with rainforest. Whenever they cross the road, they leave telltale signs that experienced hunters can track.

At the peak of their hunting activity, this dirt road was such a treasure trove of pangolin tracks that each visit would almost always result in a successful capture. They were so successful even neighbouring villages heard of their prowess.

Still, pangolin trading is not part of their traditional lifestyle.

“In the past, if we felt like eating pangolins, then we will go hunt for it,” says Anjang. “It’s not like we hunt and eat it all the time.” The pangolin is so rich in mythology among the Temiars that some of the villagers tell of oral traditions that prohibit its hunting and eating. Anjang and Ramli themselves have recently stopped hunting them, citing objections from village elders and traditions.

“When there are outsiders who want to buy it from us, that’s when we hunt it and we sell it. If there are no buyers, we won’t hunt it,” says Anjang.

Even among these communities living in the forest, who only have tenuous links to the mainstream cash economy, the trade of pangolins is influenced by market forces as much as anything. Different buyers offer the hunters different prices, and even then it changes by season. Hunters simply try to sell to the highest bidder.

“In the past, prices were around RM300 per kg,” says Anjang. “Sometimes, up to RM350. Even up to RM600.”

“But now, it fetches around RM100 per kg, maybe RM150 or RM50 per kg. If we hear the price is RM50 per kg, we don’t bother. But when we hear the price is RM300 per kg, that’s when we go hunting.”

Back at their village, a small hamlet on a low rise among towering rainforest trees, we share a meal of forest squirrel and tapioca with our hosts in one of their bamboo huts. They are still in high spirits, while we are aching with fatigue after half a day hunting and foraging with them.

When they showed us the squirrel that is now our dinner, dead from a poisoned blowpipe dart, we were told not to laugh or joke. No reason was given, but it struck us as a sign of respect for the utility of the forest and its creatures.

Do you know where the pangolins are sent to? we ask. Anjang and Ramli shake their heads. “Don’t know.”

“The middleman once told us he sends it to Thailand, that’s all,” said Anjang. “Even in Thailand we don’t know where it is sent to.”

Anjang and Ramli, two brothers from the indigenous Temiar community, are squatting by a dirt road that runs through a plantation area, pointing at what they claim are pangolin tracks.

“Here, these are its claw marks,” Anjang says carefully, fingers hovering above the soil. “It went this way, you see?”

We could not see. To our eyes, it was just loose soil and some leaves. As Anjang tries to help us discern the tracks, Ramli is already waist deep in undergrowth, following the trail. The tracks were too old, though, and he returned empty handed.

The Temiars are an indigenous people group whose traditional land sits on the northern edges of Peninsular Malaysia’s central forest spine. Even though Anjang and Ramli’s village is in the heart of the jungle, they and their hunting entourage would travel almost an hour by motorcycle to this stretch of dirt road to hunt pangolins.

“All of this used to be jungle,” says Anjang of the hills around us, now stripped of its original rainforest and terraced for cash crop trees like rubber or oil palm. But those cash crops were never planted, and our indigenous guides don’t know why. They do know that it has turned the place into an easy hunting ground for pangolins.

“They cross this road to look for food, then head back there to sleep,” says Anjang pointing at a distant hill still covered with rainforest. Whenever they cross the road, they leave telltale signs that experienced hunters can track.

At the peak of their hunting activity, this dirt road was such a treasure trove of pangolin tracks that each visit would almost always result in a successful capture. They were so successful even neighbouring villages heard of their prowess.

Still, pangolin trading is not part of their traditional lifestyle.

“In the past, if we felt like eating pangolins, then we will go hunt for it,” says Anjang. “It’s not like we hunt and eat it all the time.” The pangolin is so rich in mythology among the Temiars that some of the villagers tell of oral traditions that prohibit its hunting and eating. Anjang and Ramli themselves have recently stopped hunting them, citing objections from village elders and traditions.

“When there are outsiders who want to buy it from us, that’s when we hunt it and we sell it. If there are no buyers, we won’t hunt it,” says Anjang.

Even among these communities living in the forest, who only have tenuous links to the mainstream cash economy, the trade of pangolins is influenced by market forces as much as anything. Different buyers offer the hunters different prices, and even then it changes by season. Hunters simply try to sell to the highest bidder.

“In the past, prices were around RM300 per kg,” says Anjang. “Sometimes, up to RM350. Even up to RM600.”

“But now, it fetches around RM100 per kg, maybe RM150 or RM50 per kg. If we hear the price is RM50 per kg, we don’t bother. But when we hear the price is RM300 per kg, that’s when we go hunting.”

Back at their village, a small hamlet on a low rise among towering rainforest trees, we share a meal of forest squirrel and tapioca with our hosts in one of their bamboo huts. They are still in high spirits, while we are aching with fatigue after half a day hunting and foraging with them.

When they showed us the squirrel that is now our dinner, dead from a poisoned blowpipe dart, we were told not to laugh or joke. No reason was given, but it struck us as a sign of respect for the utility of the forest and its creatures.

Do you know where the pangolins are sent to? we ask. Anjang and Ramli shake their heads. “Don’t know.”

“The middleman once told us he sends it to Thailand, that’s all,” said Anjang. “Even in Thailand we don’t know where it is sent to.”